3rd June 2022

Interview

13 minutes read

If the elites lie to you about this, they can lie to you about anything

3rd June 2022

13 minutes read

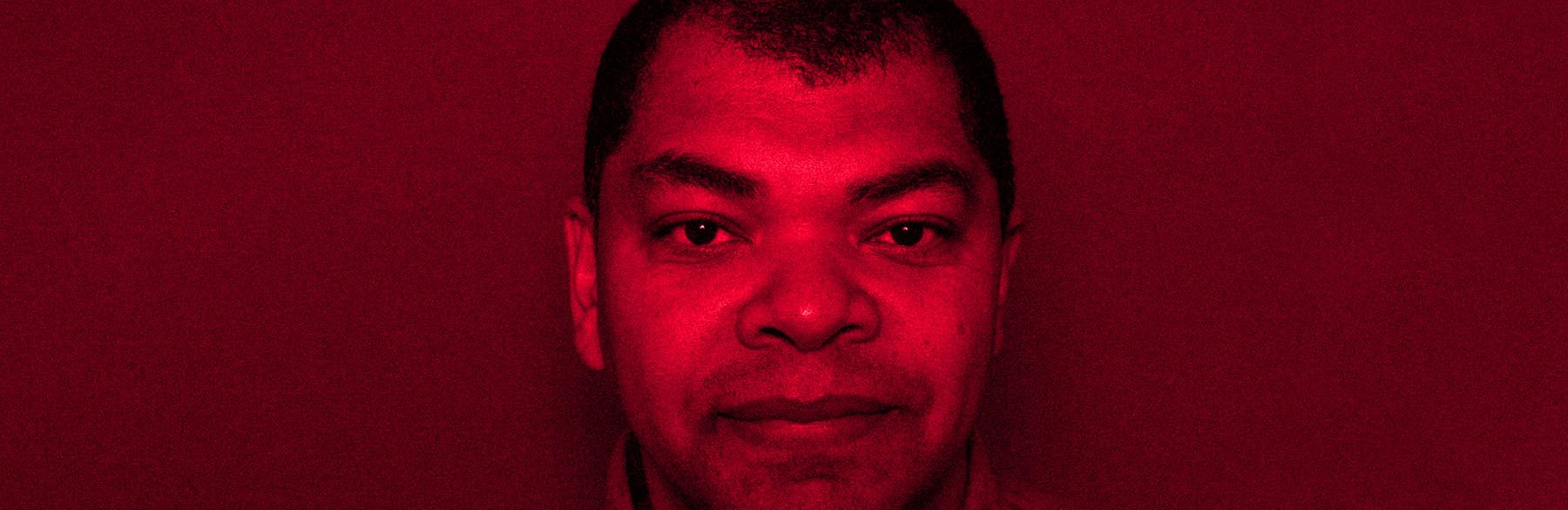

Czech writer Tomáš Zmeškal on how Czech society reflects on its history, and whether perceptions of ethnic and racial minorities have changed.

Jolyon Naegele: The son of a Congolese father and a Czech mother, you were born and grew up in communist Czechoslovakia before leaving the country for the UK in 1987 at the age of 21. You studied English language and literature at Kings College, London, and then after more than a decade abroad, you resettled in Prague in 1999 and wrote three novels in short order. The first of those novels, Love Letter in Cuneiform Script, about the half-century in communist Czechoslovakia since the end of the Second World War, won the EU Prize for Literature and the Josef Škvorecký Prize. You remarked in an interview in 2008: “the Czech way to do things is to forget.” How well, in your view, has Czech society coped with the changes it has undergone over the more than three decades since the collapse of communist rule, and has society forgotten failed to grasp just how dysfunctional and underdeveloped this country had become under Communist misrule?

Tomáš Zmeškal: “When I lived in England, there was a survey every couple of years that showed that a quarter of all children didn’t know who Winston Churchill was. So there is a general tendency to forget history but I think what has happened is that there is a competition for whose view is going to be accepted. In this, the media and academia are crucial. It’s sad in a way. A lot of people who have the experience have no way to pass it on to anyone else unless the media or academia step in. On the one hand, we have these very old witnesses of the communist era and on the other hand, there is competition over how their memories are going to be preserved and used. The great danger is that one side is used by certain politicians for their own purposes, while certain politicians on the other side would be glad if the past would be completely forgotten. Personally, I am not very happy with either of these positions.

My grandmother brought me up just to ignore communism. I remember how she said she and her family didn’t understand the era. There’s a huge amount of people like that, people who were not ‘political animals’. We’ve never heard about them, how they struggled through. You hear about people who were ambitious, intelligent, who wanted a career – they had to deal with the system. But my grandmother and my mother were accountants, which was not political. The problem is how can one preserve these kinds of family histories, personal experiences of people who were rather unimportant. From a very young age, I’ve been interested in culture, so I know how culture deals with that – in literature, in theatre, in movies, and so on, but as I get older I’m much more interested in the small experiences of the kind of people who were unimportant. I don’t think we have enough distance. I think that some people from academia try to deal with this as a kind of academic research. Some of them, whom I know personally, are so terribly scared that they really won’t talk about it because they don’t want to get mixed up in a political fight. So they do official research, which is accessible and which is good, but the closer you get to the present, the greater the danger is that someone notices and tries to interpret it to their own advantage. I noticed that some of these people got really burnt in the 1990s. I don’t share the view that ‘if you don’t know history you are condemned to repeat it.’ Rather, I share a different view, that ‘history doesn’t repeat itself’ and ‘only bad historians copy from each other.’

My first book published in 2008, deals with the history of the 1950s; one of the main characters gets into a position in which he tortures other people. After I delivered a public reading, a girl in her twenties came up to ask me to sign her copy of the book. She said, ‘You know, my grandfather did this.’ She knew he had been in the StB, State Security, the communist-era Czechoslovak secret police. From reading the StB files she found out that her grandfather was one of the people who tortured political prisoners. She said she was very frightened by what she found and that she was completely shattered for months after she had read the files about her grandfather but then she said ‘I still love my grandfather.’ How can you deal with this? What we would need is some kind of truth and reconciliation commission as in South Africa, something similar, you can’t copy it. That’s never really happened here.”

And now it’s almost too late.

“Now it’s too late, not almost, it’s too late, full stop, because the witnesses are dying or dead, so we didn’t have this reconciliation, we don’t have shared feelings for what happened.”

To what extent have you experienced or witnessed any evolution in Czech society’s perceptions of ethnic and racial minorities?

“When I returned to the Czech Republic in the late 1990s. I worked as a teacher and translator. One morning, some nine-year-old children were waiting in front of the school and one of them asked me, ‘Sir, what’s the time?’ Before then, he would’ve assumed that I’m a foreigner and he wouldn’t have asked me, but suddenly I wasn’t seen as a foreigner. Sometimes the change is received negatively. I was talking with a friend of mine at a party and he asked me if we Czechs have some kind of problem with racism. There was someone else at the party, who was completely innocent and didn’t comprehend that there are some people who have a really big problem dealing with issues concerning ethnic and racial minorities. But then in 2015, the refugee crisis hit, and the populists and neo-fascists started to get involved so now it’s a different situation than before. Up to 2013/14, I had the occasional experience of racism but it wasn’t an issue for social discussion. In 2015 or ‘16, two of my books were published in Croatia and I was invited there at a time when there were these huge columns of refugees at the borders. The Czech government was refusing to accept any refugees. Certain features of the Czech mentality, of Czech society or heritage, are a kind of innocent though quite brutal conformism. Czech culture, literature, music, and movies are liked in Croatia and they couldn’t understand the Czech refusal to admit refugees and migrants. One Croatian journalist told me, ‘You know until I read your book, I didn’t understand the Czech position but now I understand it.’ That was a very ambiguous compliment since I had written the book ten years before the refugee crisis.

There is much more to this issue. Why does the Czech government play this card? The point is that people let the government play this card. For example, the top figures of the Roman Catholic Church accepted it and went along with the government. I don’t know if that stems from this country not having had a reconciliation; there may have been other issues. I’m really interested in whether Czech society is going to split up into different segments which will continue to live their lives separately from other parts of Czech society.”

Not only here in the Czech Republic. You see this elsewhere in the United States, in Germany, Austria, and Slovakia, etc. But if we look at the Czech Republic and racism in this country, beyond the obvious aspects of ignorance and inexperience, because this is an overwhelmingly white, mono-ethnic society, the presence of foreigners residing here in large numbers and who are not military occupiers, is a relatively new phenomenon. So what is at the root of Czech racism, of these attitudes?

“In my view, there are probably two reasons for that. The first one is the expulsion and killing of the Jewish people, Jewish Czechoslovak citizens… Suddenly a very important minority of Czech society disappeared overnight and the country became mono-ethnic and also after the Second World War over 2.5 millions of German was expelled from the country, so here we are. The other root of these problems is that Czech society has several kinds of official or semi-official myths. For instance, most Czech people look at the First Republic between the two world wars as if everything was perfect. The other myth is the situation during the Second World War in the Nazi German-imposed Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and then the reunification with Slovakia at the end of the war and this is so touchy I really don’t know how to talk about it because on the one hand, official myth tells you that the Czechs were victims of the Nazis and that General Ludvík Svoboda’s army under the Soviets and the Czechoslovak pilots in the British RAF together with the Allies liberated the country. But until what the Czechs call the ‘heydrichiáda’, the brutal Nazi crackdown on Czech society in the wake of the assassination in Prague in 1942 of Acting-Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia Reinhard Heydrich, you had industry in the Protectorate that was working at full strength for Nazi Germany and the majority of people here were mostly unaffected by the war.

Another one that saddens me is how we treat the memory of the Czech soldiers who fought in the First World War for the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They were not in the Czech legions which were mainly in Russia, Italy, and France. We in Czech society do not know how to make this kind of reconciliation. Several years ago I read an article by someone at the Czech Military History Institute. He said that Military History Institute represents the best tradition of the Czech Army and that the institute’s historians consciously decided that they would start with the legions. One journalist asked him, ‘what about the Czechs who fought on the Austro-Hungarian side?’ And the military historian said, ‘well, we chose not to include them because we think they are not so important for the Czech army tradition.’ If you go through Czech villages, you see small monuments to people who fell on the side of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The reason is that the modern Czech state tries to separate from the historical fact that for centuries this country was part of the Habsburg empire. The danger is that unless there’s common ground for reaching a mutual understanding, that there were people who fought for independence from Austria-Hungary and others who wanted to be part of that empire. They were both people of this country. The extremists will take advantage because they can easily misuse it. You know the line: If the elites lie to you about this, they can lie to you about anything. You know the rhetoric.

What impact, in your view, has the Black Lives Matter movement and the killing of George Floyd had on Czech society in terms of perceptions and misperceptions, including in the news media and social media?

There was a big discussion about tearing down statues, as a Czech and partly as an art historian, which is my other qualification, I’m against tearing down statues. My father is from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and in Congo, there are statues of Belgian King Leopold. The history of Congo includes his brutal colonial regime and his statues are everywhere. I’m not against there being statues of Leopold, the problem is that when I did my research in Belgium, I didn’t find any statues of his victims. They should be in the same important places as the statues of Leopold.

The discussion of Black Lives Matter in the Czech Republic is peculiar. This is really a comedy of errors, confusion, misconception, and outright lies. Some parts of the Czech media which are violently or passionately against tearing down statues in the US of Confederate leaders and slave-owners don’t mention that we don’t have any statues left of Stalin or Lenin. Obviously, times are changing and so are statues in this part of the world.

In terms of Black Lives Matter, it seems to me that the Czech media is locked in a rather strange position. The US is still the only superpower. When the superpower which you look up to is in trouble your position is weakened. Former President Václav Klaus said ‘We are better and more democratic than the US.’ Part of the problem is that we don´t have an authentic left-wing party. We have only the center and the right. Czech social democrats until very recently didn´t care for the weak and the poor people for example one of their MPs moved to the far-right party. So we have only centrist and the right-wing parties and both are moving to the right, and they perceive even solid US or EU centrists as being the left. This is simply a bizarre situation here. There are certain trends and one of the goals is that the Czech Republic would leave the European Union so as not to be forced to fulfill any obligations.

The issue of Black Lives Matter has become an ideological pretext widely disseminated in Czech society. At an everyday level, some people, though not officially, compare the position of Afro-Americans in the U.S. with Roma in the Czech Republic. However, this comparison does not hold up under any serious scrutiny. Paradoxically, I’ve seen only a couple of indications that anyone here really understands. There is the case of a Roma man in Dečín, Stanislav Tomas, who died on June 18, while being subdued by the police, who stepped on his neck. The interior minister and the government declared that they believe the police account before the incident had even been investigated. With parliamentary elections coming up October 8-9, the mood is getting much worse. The governing parties feel threatened. The government is incapable of dealing with the current crises, the biggest of which is the Covid-19 pandemic. But the performance of the opposition was also nothing to be proud of. In part, the fault is that people want security, which the government cannot ensure. The government has to pretend that it is competent. But crises are situations for which one can’t sufficiently prepare. It comes down to how we lead our lives and what we expect from our politicians. It’s also about being a small, vulnerable nation.