10th November 2022

Fiction

7 minutes read

I Rocked Up and Down on the Branch a Bit More

translated by Thomas Cooper

10th November 2022

7 minutes read

When my mother told me I was callous and cruel, I was shaken, because I had already been a bit unsettled by the thought myself. She said it calmly. Not in a fit of anger. Like someone who had pondered the question carefully. Thought it through.

“You don’t love anyone. Or yourself. You’re callous and cruel.”

I didn’t take my mother too seriously. My father was more than enough for me, but I had come to a similar conclusion myself at the time, which is perhaps why I was so shaken by what she had said. I wouldn’t have minded being callous and cruel. Evil isn’t so black and white anymore. But that I didn’t love anyone? That hit home.

“If you don’t love yourself, you can’t love anyone else.”

“Calm down, mom, I love myself.”

I expected her to say I was selfish, but she didn’t do me that favor.

“I’m on call. Your father’s not coming home today. Don’t forget to pick up lunch.”

I sat at the kitchen table munching on my morning bread roll and reading Camus’ The Plague, though I knew my mother didn’t like it when I read at the table. She touched my hair with two fingers, so lightly I could barely feel it, not tousling it or anything like that, because she knew I would just pull away.

“See you in the morning. Bye.”

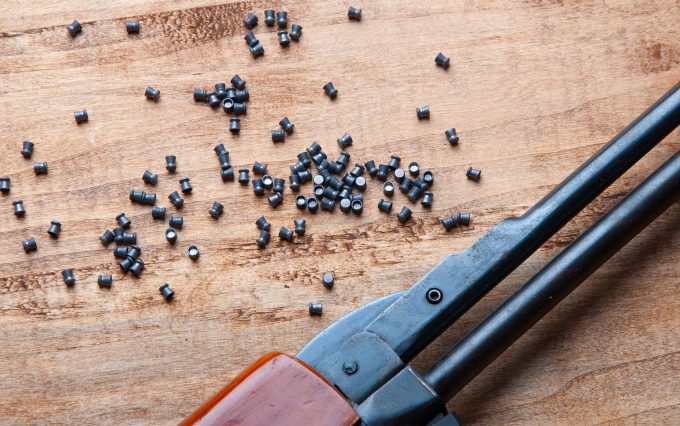

The plague interested me. And the wars. Shortly after my mother had left, I grabbed the air rifle, ran down to the basement, through the slat-wood doors, and climbed out of the window of the laundry room at the back into the hospital yard. Crouching down, I crept along, taking cover behind the lilac bushes, and then crawled through the tall grass to the edge of the incline. Before five minutes had passed, the big door of the two-story building opposite, our building, opened. First, he just stuck his head out and peered cautiously around. Then, he came out, the kid I was waiting for. Thomas Smiley. That was his name.

He was a hefty, pudgy kid.

He never smiled, his name notwithstanding. He either grinned derisively or snarled. I took aim. I waited for him to turn around and head for the boiler room, and then I shot him in the back of the neck. He flinched, let out a shriek, and started running. I reloaded. I aimed for the middle of his back, between his shoulder blades. “This is for you, traitor!” He screamed and flailed, throwing up his arms as they do in the war movies. I crawled back under the lilacs, climbed into the basement, and latched the window behind me, and ran down the dark hallway, up the back stairwell, into the apartment.

I’d been chewing on exactly the same thing my mother had said for weeks myself. I didn’t put it quite the same way she had, but the point was the same. That I was a bad person. I don’t believe in anything. I can’t even feel love. It had never occurred to me until then that I didn’t love myself, but as soon as my mother had said it, I immediately agreed.

“Yes, mom. I hate myself.”

When I was alone, I held my orations out loud. To get the words out, so the sentences wouldn’t just swirl around in my head. So that I could hear them spoken.

“Exactly, mom. You’re right, mom. I hate myself, mom. I don’t love anybody, mom. That’s just the way it is, mom. I was born this way. Should I shoot myself in the head? The rest of you, you’re good people. Dad’s not just good, he’s fucking smart. He’s flawless. And you’re a doctor. You’re good as part of your calling, your profession. Everyone around me is good. I’m the only mean one. Ugly too. That’s the hand I was dealt.

You can despise me, pity me, deride me.”

I swallowed the last bite of the buttered salami roll my mother had made for me, drank the last gulp of the tea my mother had poured into my mug, plucked the remaining pellets, the kind I had shot at Thomas Smiley, from my pocket, and carefully rolled them back into the box. The tiny, red rubber balls were made in France, and there was only one place you could get them in Hungary, in Pest, the Märklin shop on Váci Street, and even they didn’t always have them in stock, so I used them sparingly. I needed Camus. I grabbed my book, locked the door, hung the key around my neck, and went down to the courtyard. I hesitated for a moment, considering where to get comfy, and in the end, I climbed up the thin iron ladder bolted into the wall to the flat roof of the boiler room. There were a few of us who liked to go up on the roof to daydream and hatch plans. The bigger kids played cards and smoked cigarettes, because if you were up there on that roof, no one could see you from anywhere, but you could see just about every corner of the hospital: the ornate wrought-iron gates of the former manor house, the walkways and parks, the residential buildings, the playground, the tennis courts, the garden shed and the incinerators, the nurses’ lodgings and the garages, even the forest edge. I sat down on the roof, which was strewn with pebbles, leaned back into the shade of the huge brick chimney that stretched skywards, and spent half the morning in Oran, where it is difficult to die, or rather unpleasant.

It was past eleven when I noticed Kornél Bátor ambling along, quite far away, in front of the crumbling whitewashed wall of the old incinerator. He kept stopping and glancing back to see if anyone was following him. Then he crouched, lay down flat on his stomach, and plunged his right hand deep into the throat of one of the old building’s rusty gutters. When he’d finished, he quickly climbed to his feet. Now he was in a hurry, and he was trying to look as innocent as possible and get away from the scene of the crime as quickly as possible. He walked past the elderberry bushes and the lilac grove, then hurried down the dirt road lined with bedraggled poplars, towards the garages, past the tennis courts and the nurses’ lodgings, until he finally disappeared behind the swinging glass door leading to the staff quarters.

I waited a bit and then climbed down the rusty iron ladder.

I took the shortcut, going past the garden greenhouses towards the old incinerator. I lay down on my stomach, reached into the gutter, and found nothing. I strained hard, pushing my arm into the rusty pipe all the way up to my shoulder.

“Looking for something?”

It was Kornél’s voice. I had to pull my arm free to turn around. He was leaning against the wall a few meters away. He didn’t smile. On the contrary, he looked like he was taking the whole thing pretty seriously.

“Or do you just go reaching into the drainpipes every now and then?”

“Fuck, Kornél, when did you catch sight of me?”

“I didn’t catch sight of you.”

I gave him a blank stare.

“It was just a test. To see if anyone was watching.”