8th February 2022

Fiction

8 minutes read

In Front of the Mirror

translated by Julia Sherwood

8th February 2022

8 minutes read

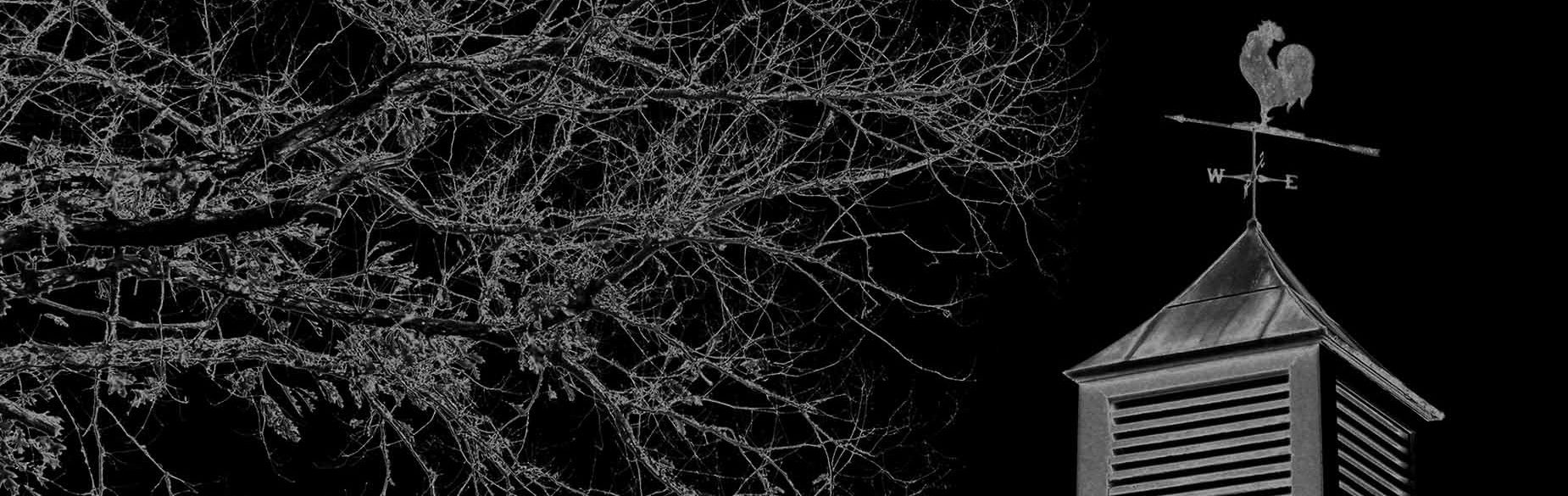

Some things are clearly visible even if they take place in the middle of the night. The peak of the spire, topped with a rusty revolving rooster, affords a view of the square and the adjoining streets. The gently creaking rooster’s field of vision takes in the whole of the tranquil and unexciting town of P., located somewhere beyond the range of interest of the news agencies, on the edge of the civilized world, although the locals pride themselves on being part of a civilized, law-abiding Europe—not the barbarian steppes.

It is evening, early October 1928: the town festival. As it spins around in the wind, the rooster on the spire sees men, dozens of them, storming out of the bar, carrying justice in their hands – hoes, sticks, metal hooks, knives, revolvers. They chase their victims around their own houses, down the streets and into the fields surrounding the town. They leave behind scalped heads coated with feathers from torn pillows, elaborately tortured remains, body parts, the corpse of a six-year-old girl shot before her mother’s eyes. Through a gap between the boards of a summerhouse, lit up by the moon, a lifeless, single bulging eye stares up at the rooster.

The unprovoked brutal torture and killings have been unleashed on their neighbors by hitherto timid and irreproachable local clerks, teachers, merchants, the mayor, and members of the local council. After a few hours the frenzied operation comes to a halt, as if a curse had spent all its force. The air clears, the streets and fields fall silent. The tools are rinsed, the bodies dumped in some unknown place.

The locals have no explanation for what has happened. No one remembers the details. The only thing that’s certain is the whole operation went smoothly, without a glitch or any attempt to put a stop to the frenzy.

Investigating officers fail to get to the bottom of the event, most likely because they have no intention of getting to the bottom of anything. But even if they approached their task conscientiously, a different outcome would be beyond their capabilities. No one heard anything, or saw any proof of the murders. The witnesses get tangled up in their testimony, only to deny everything again while each day – without pointing their finger at anyone in particular – they come up with some new implausible claim and spout blatant nonsense that won’t stand up as evidence.

The clergy and the police side with the perpetrators, accusing the victims of trumped-up offences. In the end no one is charged with the murders: there are just three symbolic indictments for disorderly conduct, and the whole business is forgotten. Years later there is nothing that might commemorate the event. No symbolic crosses for the victims, not even a plaque somewhere out of sight or a single mention in the town chronicle.

Subsequent conversations with the reticent and reserved residents of the town lead to the conclusion that no one bears responsibility for these acts, and a few days later hardly anyone even believes that they actually took place. It couldn’t have happened that way; it can’t be true.

Why? To be honest, I knew you must have come here for a reason. No one ever visits this place out of the blue. I’ll serve you your beer, I’ll even have a drink with you, if I may, but as for these events, the only one you can ask is the rooster, he’s the only witness. And while we wait for him to sing, let me introduce you to our town of P. I’ve been running this local pub for a hundred years now and nothing has ever changed. The same people live here, and they all think the same way, even if they have turned in their graves several times, as I have done.

If you took a walk around the streets of our town and had the time to crisscross every single one of them, you’d probably reach the disappointing conclusion that P. is a pretty average and tedious place, hardly worth visiting. It has no historical monuments to speak of – unless you count the church and the multistory dump that passes for our town hall. Equally devoid of any interest are the regulation tenements, the murky little river V, the pond, and the marketplace downtown with nothing to offer that you wouldn’t find anywhere else in the world. P. can’t boast of its atmosphere either: the people in the streets are mostly taciturn and grouchy, and aside from a few cheap bars there is basically nowhere for a visitor to kill time. That’s why every stranger is treated with suspicion. You say you have come as a tourist, but I can tell that you intend to pry, slander, dish the dirt, spread untruths, and speculate. Come on, what else could you possibly be interested in other than the wretched year of 1928?

Because nothing much has ever happened here in P., apart from that armed hounding of the Roma. What history has ever occurred here? What has history got to do with us? Other than the odd exhibition of folk embroidery, or the time we made it to the finals of the Village of the Year competition, but I guess that’s not what you’re interested in.

History is nothing but things you can’t verify. Idle talk of those who hold a grudge. Let me give you my opinion of that event, because my opinion is my truth.

P. has always been a calm, sleepy, and lethargic place. People here are like purring lions with their bellies stuffed and eyes half-open, wagging their tail or batting a fly away every now and then before padding off nonchalantly into the shade, one paw after another. The locals do stir, but their manner is so lethargic that if you observed them from the top of the church spire, you’d find it hard to tell whether you were looking at a photo or watching a film.

Back in the old days I would have sworn that this was the calmest place on earth. Nobody missed anything because they never thought about anything. However, that can’t have been the case: the past was bound to conceal something, as it was a past that went back much further than my first days in this world, a past no one remembered, or wanted to remember, or had been prohibited from remembering. A very long time ago something must have happened here that silenced everyone, sapped their strength and energy, extinguished the spark in their eyes, and wiped clean their memories. An outside observer might have gained the impression that this is an idyllic and contented place, but in fact what they see is just ordinary apathy. The silence comes from locked tongues that are under the spell of deep and long-term shame and guilt, which, if allowed to bubble to the surface, would make it impossible to breathe.

Nothing disappears from this world just like that. The past will start to seep through, filling the air with tiny droplets of tension, energy will slowly emanate from the earth. Ghosts that had been unhappy and unreconciled for decades started to articulate threats that were increasingly easy to understand. Once again, ancient forces brought forth something stifling, something that enveloped us. We found it hard to breathe, our lips twitched nervously, our skin was itchy. And words followed suit. A valve had been released. The sky, the boundless, oppressive sky, pressed the people of P. to the ground like the lid on a pressure cooker.

Then October 2nd arrived, and all hell broke loose.

We are not a people of a violent disposition. I’m not sure whether I’m saying this in our defense or as an argument against us, but we have always known our place. Someone else has always had the upper hand, be it the Hungarians, Austrians, Czechs or Russians, and we have always toed the line, peering from behind drawn curtains to check what’s happening out in the street and actually quite happy to be ruled by someone and not have to make our own decisions or settle our own accounts. It’s hard to go on a killing spree when you’re a prisoner.

The only ones we’ve had the guts to take on have been the Jews and the Roma, that’s what our circumstances have allowed. We are a small people, surrounded on all sides by larger nations. Someone might use the term cowardice in this context, but self-interest would be more appropriate. We’ve had to pick someone safe to hate, comfortably, without risking retaliation.

FULL VERSION AVAILABLE IN THE PRINT EDITION.