27th October 2022

Fiction

6 minutes read

The Red Light

translated by Mark Ordon

27th October 2022

6 minutes read

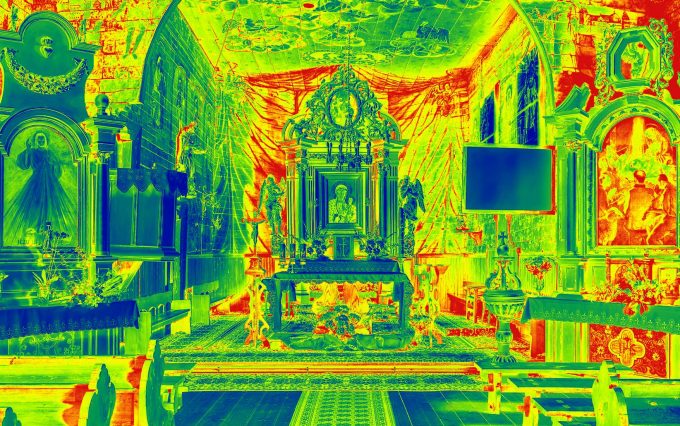

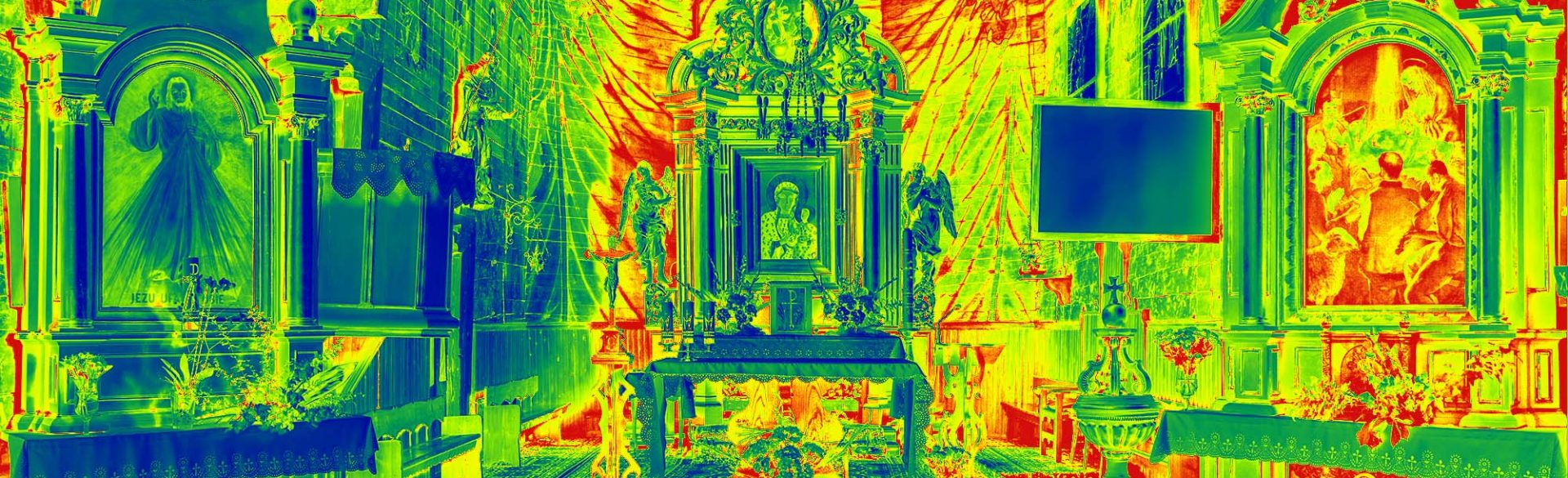

Grandma Albina believed that God spoke to her through the thermal imaging camera that was installed during the renovation of the parish church in Żory. There were at least a few in place throughout the building, but my grandmother was particularly attached to the one in the left nave, right next to the painting of Christ the Merciful. The red indicator blinked in a discreet hue—on, off. Grandma would be immersed in her prayers, petitioning the Lord, asking Him to bestow good health on her husband and common sense on her daughter, to support her grandchildren with their school work, to keep her healthy–just a little bit longer, Dear God, just a few more years until the kids go to college—and when she opened her eyes, she would glance at the light. If it was on, her prayers would have been heard.. If the light was off, she would become depressed. I have no idea what she did with those unheard prayers. Did she try them again? Probably.

She was a pious Catholic, but nothing extreme.

She attended church every Sunday, or actually, Saturday, because the evening mass on Saturday already counted for Sunday, and no use waiting to fulfil one’s obligations, she would say. She also attended the May devotions to the Blessed Virgin Mary, just under an hour every day for the whole month. I’m sure she wasn’t a zealot or anything like that. She never listened to Radio Maryja, the largest Catholic media outlet in Poland, generously supported by the right-wing government. Rather, she would tune her antenna to Polish Radio One every day around noon to hear the Heynal from Kraków, which was as much a part of her routine as her daily episode of The Bold and the Beautiful.

Her religiousness was rather folksy, not too profound, with a strong attachment to rituals. And probably, more so than the Father or the Son (no one really cared about the Holy Spirit), she preferred the Mother of God. She would often recall her miraculous image in the church in Bielany. Though truth be told, it was the image of Jesus Scourged that was supposed to be miraculous, hidden under the image of Mary. But what could a bruised thirty-year-old do for a little girl who was desperately missing her mother who had died too early to even be remembered? In Grandma’s stories, Bielany was located in some wondrous other world that took hours to get to in a horse-drawn cart: on Google Maps it’s 1.4 kilometers, fifteen minutes by foot.

That’s how grandmothers were, they knew those weird prayers and songs by heart;

without them, everybody would have long since forgotten all that Catholic stuff. But that light. It was dreadfully kitschy. Miraculous images, the smell of incense, sure. But a thermal imaging camera? Albina didn’t seem to care. In that red blinking light, which in the best of cases could have made a pair with the red light of the tabernacle that went out just once each year, on Good Friday, Albina saw the capricious eye of God.

That really irritated me. Just a little at first, as an oddity of an elderly person, but my irritation grew over time, until I finally concluded that it was sacrilege. That was around the time when I decided to become a priest.

I was about fourteen or fifteen years old and had already been initiated in matters of alcohol, sex, and electric guitars. I was reading a lot then—Marquez, Vonnegut. Church was no concern of mine. That was Grandma’s thing. We, meaning my mom, my siblings, and I, had a rather utilitarian approach to religion. We were all baptized and went to First Communion, but we showed up in Church on holidays only. Yet from a formal viewpoint, we were Catholic; I attended catechism and went to retreats organized by my school before Easter– three days of intense religious teachings, given at the church for a change.

We enjoyed those three-day sessions because spring was at the door and we didn’t have regular classes. So we would plan to do things after church— play ball, have a beer in the woods. Things took a bit longer on day three of the retreat because you had to go to confession. The lines were long and extended all through the church. When it was my turn, something came over me to just tell it as it was. And maybe the priest had a bad day, maybe something else just tipped the scales. I didn’t even get to my list of sins, I just said,

“It has been twelve months since my last confession,”

and he interrupted me. He said that if that was the case, there was nothing more to be said, and he would not grant me absolution. Then he offered me a deal: if for the next two weeks I attended evening mass every day and rethought my attitude toward faith, then I can come back. His voice became more gentle as he said these words, and maybe that was what convinced me; he added that I could of course cheat, go to another priest and receive absolution, but he believed that I would be honest about it.

His words touched on my ambition. Or on my fear. Either way, I took them seriously. And that’s how it started. I attended mass regularly, maybe not every day, but certainly every Sunday. I fasted on Fridays, and not only did I refrain from meat, but also from parties with my friends. I even bought myself a rosary. And I read a lot, got caught up on the Bible and the catechism of the Catholic Church, a heavy blue volume that contained everything.

When I imagined becoming a priest, I aimed for nothing less than bishop.

Sounds like the inklings of fundamentalism, but I simply wanted to ace it. I wasn’t interested in amateurism, like those religious youth groups where you sing songs and pick up girls. But I did read the Tygodnik Powszechny weekly, a social and cultural magazine established in 1945, the refuge of the so-called open Church, which had more to do with contemporary philosophy and Czesław Miłosz than with folksy religiousness.

This entire matter of religion was my own thing. My very own idea for living, probably the first idea I had ever developed so consistently. It was a project that had nothing to do with the pagan religiousness of my grandmother, who would stare at the red eye of God.

I still believed it even when that entire experiment called religion was nothing more than just an embarrassing memory. I sometimes told my friends the story, but even then I stipulated that it had just been a concept, an artistic performance. No authentic religiousness to speak of.