21st March 2023

Non-Fiction

9 minutes read

The Hungarian Law That Blocked Women’s Education

21st March 2023

9 minutes read

In the early 1930’s, Margit Kovács (“Gréti”) was a typical middle-class girl in Budapest––learning to play the piano, studying French, and ice skating at Nagyrét. From a young age, she was smart. “I passed the fourth elementary grade with flying colors,” she said in an interview for the Shoah Foundation in 2000. Gréti graduated from Veres Pálné High School in Budapest, with top marks, in 1936. She had planned to do well, so she could go to college. “I wanted to be a doctor so much,” she said, “and a pediatrician at that.”

But Gréti’s dream would not be realized.

In September, 1920, a law was passed in Hungary curbing the enrollment of Jewish students in universities. Titled “Law XXV,” the numerus clausus law marked the “earliest instance of anti-Jewish legislation in Europe,” according to Judith Szapor, professor of history at McGill University, in Montreal.

The law marked a reversal of the freedoms earned in the previous, more liberal era. In 1867, Jews were officially integrated into society, becoming equal in the eyes of the law. But when the right-wing Horthy government took power in January 1920, there was a backlash. With the numerus clausus edict, a quota of 6% of admission for Jewish students, based on the percentage of Jews by religion in the general population, drastically reduced the high representation of Jewish students at Hungarian universities. And the 6% were just from the fraction of those Jewish students who were eligible to enroll.

On top of this, there was also a ban on all women at Budapest Medical School until 1926.

University administrators also cracked down on any perceived threat to the political regime by deeming “upstanding loyalty to nation” a requirement for university enrollment. Right-wing student militias sat on admissions committees, Szapor said, and could weed out any “suspected member of a liberal student organization, a participant in the revolutions,” she wrote, without even granting the applicant an interview.

The numerus clauses law was promoted by university leaders, who discouraged left-wing and Jewish applicants, and also dissuaded women from applying to universities.

Overnight, university enrollment of Jews dropped from the previous 20-30% to around 6%. Because of the law, many Jewish students were forced to either drop their plans, or to study elsewhere. Between 1920 and 1938, 10,000 students traveled abroad – to countries like Austria Italy, France, and anywhere else that would welcome them. While the law changed in 1928 to end the official cap of students, this was simply a modification “in its letter but not its practice,” according to Szapor, and university enrollments for Jews and women continued to be limited by university administrators, until the late 1930’s.

***

The future of thousands of students, like Gréti, would be disrupted by the backwards laws issued by a right-wing political regime.

In the spring of 2020, Szapor was in Budapest as a fellow at the Institite for Advanced Study at Central European University. As part of her program, she gave a talk at the university – a talk on the subject of her work: “Antisemitism, Gender, and Exile: Hungarian Jewish Women and the Numerus Clausus Law in Hungary, 1920-1938.” Sitting in the audience was Éva Karádi, former editor in chief of the Hungarian edition of the European cultural journal Lettre Internationale. Karádi and Szapor had overlapping interests, and “sort of knew each other, but never met,” Szapor recalls. After the talk, Karádi expressed great interest in the subject, and proposed teaming up to uncover these personal stories.

Karádi posted a request on Facebook to anyone who might have had a family member affected by the numerus clauses. Responses began rolling in

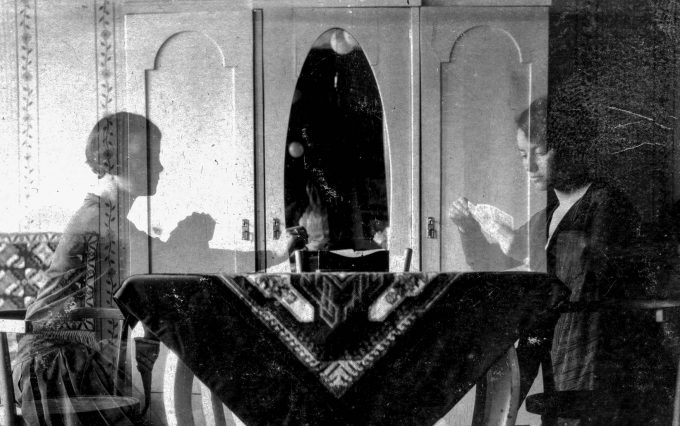

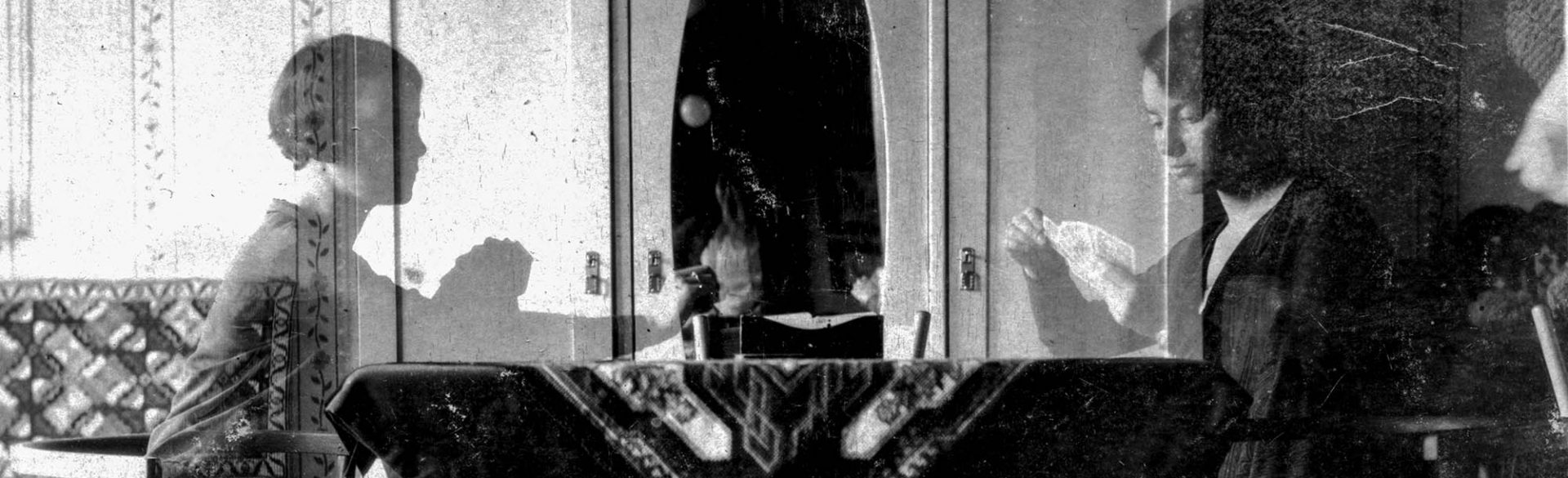

– and by the end of the project, they collected 160 participants, altogether, and more than 500 photos–

from personal collections, as well as from the photo archive Fortepan.

This took place during the period of quarantine, Szapor recalled, which turned out to be a perfect time to collect material. She and Karádi “spoke almost every day for a couple of hours,” Szapor told me. “The way it worked was that I would advance my arguments, and she would feed in all of the stories and correspondence she was having with all of these people who were all sitting at home, going through family papers and photos.

It was like a “textbook case, where the project is being shaped as you’re progressing,” Szapor recalled, which was unusual for her – she’s used to visiting the archives to gather material, or confirm her hypotheses.

In August 2021, the pair launched the exhibit at the 2b Gallery, Budapest, Hungary, funded by the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council via a Canada Insight Grant. In November 2022, the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies (BCDSS) for the Women’s Museum, in Bonn, Germany, premiered its own exhibit. The exhibits feature Hungarian Jewish women, born between 1900 and 1925, who wanted to study. “Many of them by ended up abroad, or training in a profession or field privately (Montessori teaching, psychoanalysis, the arts, photography, etc.),” Szapor wrote, and the exhibits aim to celebrate these achievements of these women, despite the discrimination they faced.

Because Karádi had spread the word among her own social network, it is not an accident that many of the subjects of the exhibition are people she has a connection with – they are her family members, her German teacher, her colleagues.

Karádi’s own family was affected by the law. Her cousins, featured in the exhibit, XYZ. But her father and mother were influenced by the law, as well. Her father was forced to study abroad, in Brno. When he returned to Budapest –he and many others who had studied elsewhere faced a predicament: “There was a question if they could use the diploma from abroad,” Karádi said. He struggled to find work as an engineer.

Despite the challenges Jewish men faced, studying abroad, the situation was worse for women. Men, at least, had more of a chance to be sent abroad. “They were afraid to send girls abroad,” Karádi explained. And there were other factors in this decision, as well – for instance, family finances. Often, birth order was important, and siblings born later had a lower chance of getting an education.

The post-war era –“that’s when they started studying, started having children,” Karádi told me. “They felt liberated.”

Some women, however, were sent to school overseas. Gréti became one of them.

“My whole life was marked by the fact that my father was Jewish and my mother Catholic,” she said in the Shoah Foundation interview.

Gréti formed a reading circle with eight other girls from school. It was during the period of the 1934 György Pikler trial – when a student was arrested for communist activity. The events shaped Gréti, and she and the other girls became self-identified socialists.

To circumvent the law, Gréti even baptized herself, without her parents’ knowledge. Still, she was not admitted.

So, Gréti left Budapest, and enrolled at the Austrian College of kindergarten teachers in Vienna, where she spent afternoons attending lectures of Anna Freud, as well as gatherings with the Austrian Social Democrats.

When she returned to Budapest, “we didn’t join the Social Democratic Party, we joined the Communist Party,” Greti recalled. “So I didn’t become a party cadre referent, but I worked for the MNDSZ. That was the Democratic Alliance of Hungarian Women, the women’s movement of the Communist Party, where they put me in charge of the education politics department. First only in Budapest, then at the national level.” She called the years between 1945 and 1948 the “best period of our lives.” In large part because of the “real friendships, real solidarity,” among her friends. “Education, knowledge were highly valued,” she recalled.

Later, she began developing an eight-year elementary school, kicking off working groups for parents. Finally, in 1954, her “post-liberation life” began. Greti could finally apply to university. She enrolled at the Department of Hungarian Language and Literature of the Faculty of Humanities of ELTE, where she later graduated with distinction.

***

Karádi and I recently met in Budapest. “This generation of women [who were affected by numerus clauses] had a very hard life,” she told me. “They wanted to study; they couldn’t study. They had to do other things instead.”

The women featured in the exhibit were skilled in many areas – but beyond that, they shared a hunger to learn. Mária Gellér published poetry as a student, and wanted to enroll in the faculty of humanities. Piroska Fischer spoke five languages – she became a seamstress. Other women became typists, repaired carpets, doctor’s assistants, milliners.

They come from a range of family backgrounds: They belonged to the elite and the lower classes; their fathers had different professions; they were from the countryside and urban environments. The one thing they all had in common was the desire to study.

***

If there was a silver lining to the law, it could be that it helped inspire a generation of activists. Other women who were banned from attending university, like Gréti, were involved in leftist movements.

Erzsi Zador was still in high school, “in the middle of taking exams” at the time of the “Red Student” trial, her daughter, Anna Perczel, recalled. Erzsi (and the man who would become her father) were jailed. She later studied in Brno. “My mother wanted to become a doctor like her two brothers, but grandfather had no money for that. So she went to a textile school.”

Anna Por was from a “prosperous middle-class family”– a situation that caused many children to “rebel,” her son, Matyas, said in an interview. Por went to France where she learned and practiced all forms of movement art, but unfortunately, was unable to get a degree – she had to wait until she returned home to Budapest after the war. “And this bothered her,” her son remembered. Still, she joined the labor movement, along with her sister, and ended up organizing cultural festivals in France for L’Humanité and participated in the Resistance.

***

Today is yesterday’s future.

It is constantly shifting, morphing, and unpredictable. But by looking at the past, we can learn about cause and effect– we can become better predictors of how what we do today will shape tomorrow.

Reflecting on the broad themes from the Facebook messages and interviews of the children and relatives of this generation of women, there was a “mixed bag,” Szapor told me. In some of the messages, there was a sense of bitterness that their mothers could not attain the education they deserved. But the overall message? “Pride,” Szapor said. “They were proud of these women, who never gave up.”

Photo credit: Fortepan / Preisich család / 157925