11th July 2023

Interview

25 minutes read

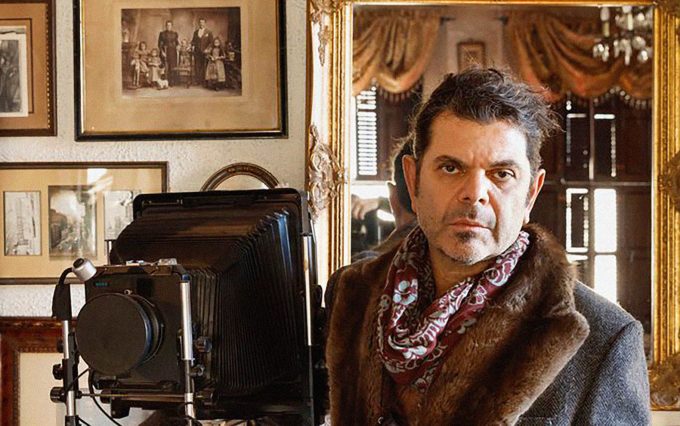

“So it’s also a matter of my survival.” – An interview with Flóra Borsi

11th July 2023

25 minutes read

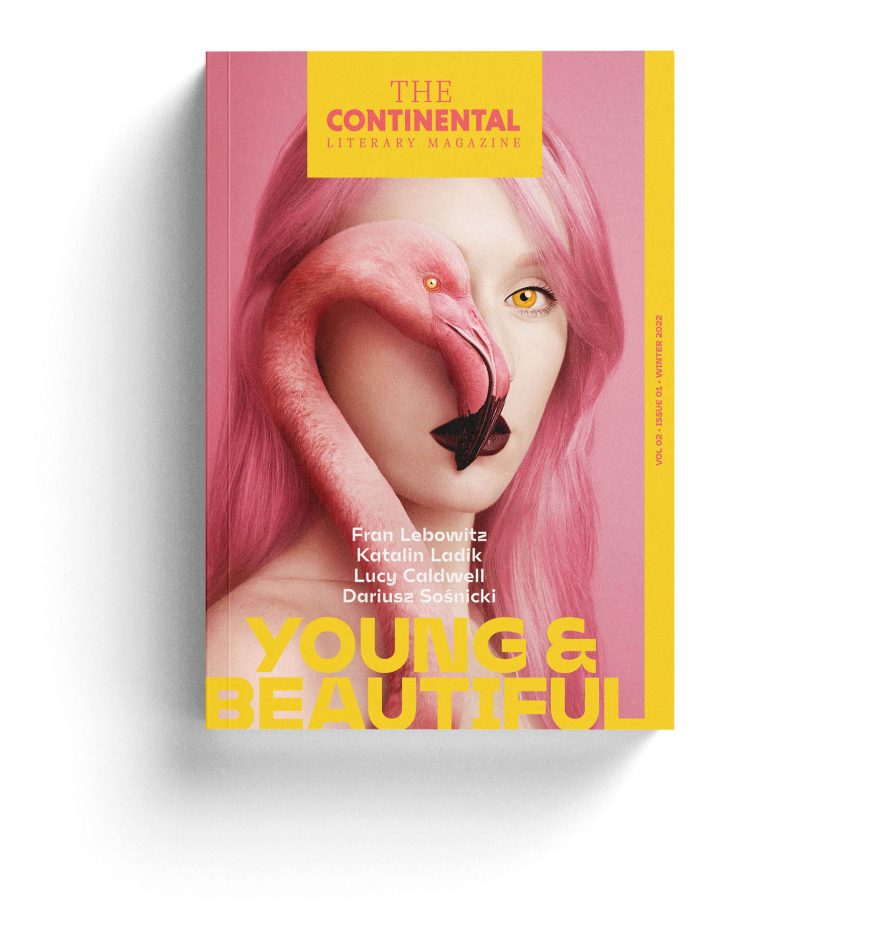

Attention deficit, synesthesia, and difficulties fitting in, are burdens in everyday life, but they can be advantages for artistic self-expression. We spoke with Flóra Borsi, photographer and illustrator for the Young and Beautiful issue of The Continental Literary Magazine, about various artistic milieus, unconventional creative processes, and the social impacts of image manipulation.

Balázs Keresztes: The title one most often hears attached to you is the “Princess of Photoshop.” How did you go from drawing as a child to having your name and art intertwined with this modern art medium?

Flóra Borsi: Since I was a child, art has always captured my imagination, with the only difference being perhaps that back then, it was not art, but play. From the outset, I was busy sculpting or sometimes sewing clothes for my Barbies. Bead weaving and things like that. Any creative activity that a child could engage in. Then I started primary school, and we had a drawing teacher, Mary, who obsessed with the idea of nurturing young talent. She noticed my interests, and I started drawing on a more serious level. I went to lots of drawing classes, and she sometimes took me out of my other classes so that I could prepare, with her help, for drawing competitions. When I was seven, we won an international drawing competition, which was quite a big deal at the time. Then I won another one, and then came the national drawing competitions. This seemed like a kind of predestination for me, because success felt so good, as did the fact that I was able to do it all with my own two hands. It enthralled me, and it felt so good to draw. It was a completely different experience for me than getting highest marks on a text in a literature class. I was ten or eleven years old when my sister, who is ten years older than I am, was doing designs in Photoshop, and I asked her to give it to me, and in the summer break I got a computer from my dad at my grandmother’s place. She was also someone with a gift for nurturing talent, and she made sure we had anything we might need for creative self-expression. And so then I spent the whole summer break using Photoshop to play with ten or eleven pictures that I had saved to a CD. This was all very exciting for me at the gentle age of eleven. I did not speak English, I knew nothing about the software, but I realized that you could transform images, and this only later became intertwined with drawing and the visual arts. At first, computer graphics and graphics done by hand were completely separate for me.

At twelve or thirteen years of age, I thought that I would become a web designer like my sister.

I started making webpages. I had a GPORTAL line, and I made webpages for my classmates. I did this until I turned 15, and then I became a little “emo,” and I started using Photoshop to edit emo images. I realized that on MyVip, which was a social media portal at the time, one could make quite a splash with this kind of thing, and several thousand people had looked at my emo images. As a teenager, I became a real emo star! (laughs) What remained of that later was that I used Photoshop to edit my photos and I took pictures of myself. Then came an unfortunate period when I was diagnosed with a tumor. Fortunately, it was benign, so I didn’t have to fear for my life. By the time I ended up at the doctor’s, however, with my 15-year-old head I had already resolved to throw the dice: I knew that this was what I wanted to do, and I wanted to be like the great photographers. Whatever happened, I wanted to be a cool photographer and leave behind a legacy of pictures. I had been accepted to a secondary school at the time for a drawing program, and I realized that I couldn’t draw very well. My classmates could draw anything they laid eyes on, but I could not. If my classmates drew a picture that could be made using three colors, they used three colors, whereas I used twelve which they couldn’t even see. That was when I realized that, since I can’t draw very well and I had this fear of passing away, I should take pictures of myself and do all kinds of surreal things too. And that was when I gave up drawing and started concentrating on photography. My father was a good partner for me in that. I feared that I would never be able to master the art of photography because the technical side seemed so complicated. When my father explained how the camera works, what the shutter speed is, and how to sync it with the flash, then suddenly it didn’t seem quite so inscrutable. I took lots of photographs of myself, but they never turned out the way I wanted them to. I realized I had to learn this craft. That was when the real photographer part of my career began, and then came Photoshop. Let me note, I am not the person who came up with the “Princess of Photoshop” title. That was given to me by others. I only use it because there’s an English girl who simply copied my identity a few years ago. To this day, if I take a picture, she does a similar one. She’s the reason why I started calling myself the princess of Photoshop, to make clear that I am the princess, not her. (laughs)

BK: That’s fate for you! You are forced to accept a responsibility that you never wanted!

FB: Yes, and I realized that if I post the images on my Instagram page, she can’t post her lookalikes. It’s a bit childish. Maybe someday the history books will write about this rivalry, like the rivalry between Renoir and Monet. (laughs)

BK: I have often been quite struck by the stark contradiction, the fact that in some places, your works have won undisputed recognition, for instance from Adobe, the very maker of Photoshop, while in others, you have faced enormous resistance, for instance in Hungary. What do you think? Was this because Photoshop was unfamiliar or had not yet been accepted as a new art form, a new medium, or would you look for the explanation elsewhere?

FB: When I started to make my images and I began to find my own voice, I was completely unprepared for the possibility that someday, somewhere I would have to meet expectations with my work. That I would have to do something about this here, in Hungary. I was doing it because it made me happy, and it was a way for me to express and live out my imagination and my dream world. At the very beginning, when I created my Facebook page, Borsi Photography, I was 18 years old. I was already using a more professional camera by then, and I had some background in the field, but what I did was still very divisive. I noticed that when I uploaded my photos to portals abroad, I wasn’t inundated with the kind of flood of negative comments that I got, say, on Facebook. I started to realize that the fact that I was using Photoshop and images of myself was something very new and also something that could easily be misunderstood or pigeonholed. In Hungary at the time, I was in the tolerated category. They thought of me as a cute little girl, 18 years old, let her do what she wants, she’ll never be anybody we have to fear professionally anyway, anybody who would ever take anything away from us. As I grew more and more serious in my work, the enemies and hostile voices in Hungary grew more and more strident. After a while, there was such a contrast between foreign countries like the United States and, especially, Asia on the one hand and Hungary on the other that I simply felt like I had two identities, and for a long time, I myself couldn’t figure out who I was.

Am I now an artist or just a little girl who takes photos of herself and does all kinds of neat stuff with Photoshop?

In Hungary, I wasn’t taken seriously, and I had no chance of getting into a gallery or exhibiting or winning competitions. The audience was divided: there was the professional community, which was extremely hostile, and the non-professional community, which was very welcoming. It used to be very hard for me to take criticism, and when there were articles about me in Hungarian newspapers which analyzed my work, it was often striking that they didn’t base their critical assessments on facts but rather simply said that what I was doing was crap. That it was claptrap or gawdy. But they could not turn my work into an ideology. I always posted something on Facebook when I was being attacked, just something saying that they were at it again, and the supportive community there always came to my defense. That’s when I realized that I should focus on them and not on the professional community, who would never accept me and would try tooth and nail to make it impossible for me to work.

BK: How did this dual approach find expression?

FB: In 2013, the camera I had won in an earlier competition broke, so I launched a community funding campaign to get a new camera. I naively posted a video in which I speak about my previous successes, my Time Travel and The Real Life Models photo series, which had just garnered a lot of attention, and I was suddenly very popular abroad, especially in the United States. And I was saving up for the new camera. The comments in Hungarian underneath the video were expressive of a level of hate that I never would have imagined, things like, “I’d rather lay bricks then beg for money.” In contrast, the comments by people writing from abroad, from New Zealand to Tasmania, were things like, “cool chick,” “people from everywhere support you,” “go for it,” “here’s five bucks,” “we hope you get the money, and the stuff you’re doing is great!” The money for the camera came together in the end, and I was able to create in a completely relaxed way. Then people outside of Hungary who were also in the profession in some way joined the Hungarians outside of the field who were enthusiastic about my work. Six months later, I had my first exhibition in the United States. I still have close friendships with the people I met there. It was a small community of artists who appreciated my work and saw the message in it, saw the concepts behind it, and realized who I am. This gave me strength, and then the importance of the other successes with Photoshop and working with the Hasselblad camera became clear to me, but for a long time, the negativity I had encountered made me feel very uncertain. I realized that, in Hungary, if someone does something that is unfamiliar, something that has not been nurtured by the professional community, then this something is received with hostility. They don’t like the new in Hungary, they like the familiar, and they certainly do not accept people who are capable of thinking for themselves and don’t try to captivate the Viennese or German public with the same kind of depictions and the same visual world that they use.

BK: One of the salient features of your work is that you photograph your own face. Looking back, what does it mean for you to be the subject of your own compositions?

FB: When I was photographing other people, somehow I always had the feeling that I couldn’t give a hundred percent of the thought that the photograph deserved. I cannot regulate my brain to make what I have envisioned work with the faces of others. My photographs are born through an association game: most of the time, the image appears in front of me, but it doesn’t work with someone else’s face. I don’t know why, but it doesn’t. I am also very afraid that what is mine will be taken from me. I have been troubled by this fear since childhood, and I think that if I work only with myself and make these images entirely on my own, no one can take them from me. It really is a one-man show, and I can only count on myself.