About the Issue

Don’t Wake the Sphinx

Humankind’s self-awareness comes at a price. We attempt to bolster convictions of our species’ greatness and uniqueness with shaky arguments: the only species to be aware of its own mortality, the only species to create culture, the only species – as in Orwell’s beast fable – to purely consume: “Man is the only creature that consumes without producing. He does not give milk, he does not lay eggs, he is too weak to pull the plough, he cannot run fast enough to catch rabbits. Yet he is lord of all the animals.” We needn’t deny that our birth right is at most to be king for a day, and the privilege brings loneliness, anxiety, and fear. In Arthur C. Clarke’s words: “Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” On our own planet, we pay this high price daily for our presumed supremacy in nature.

We’re desperately searching our evolution for the missing link that will reconnect us to the animal world and provide some reason for why, occasionally, the vicious beast flares up from within us. As deep as the answer may lie, we assume the beast never left. “It’s just the beast under your bed, in your closet, in your head,” sings James Hetfield, in Metallica’s “Enter Sandman”. In the past we placed the monster outside of us, in myths, and later we turned inwards, but since the soul eludes our grasp, we sought out never-before-seen, tangible, printable explanations. We called on biology, mapped our brains with MRI scanners, and found abnormal patterns, suggesting that antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy are linked to changes in one’s prefrontal cortex. But we tend to forget that when cornered, our animal instinct still takes over and the cultural glaze, though nurtured for centuries, vanishes. Only the strongest, the fiercest, the most terrifying will prevail; the beast has become unleashed.

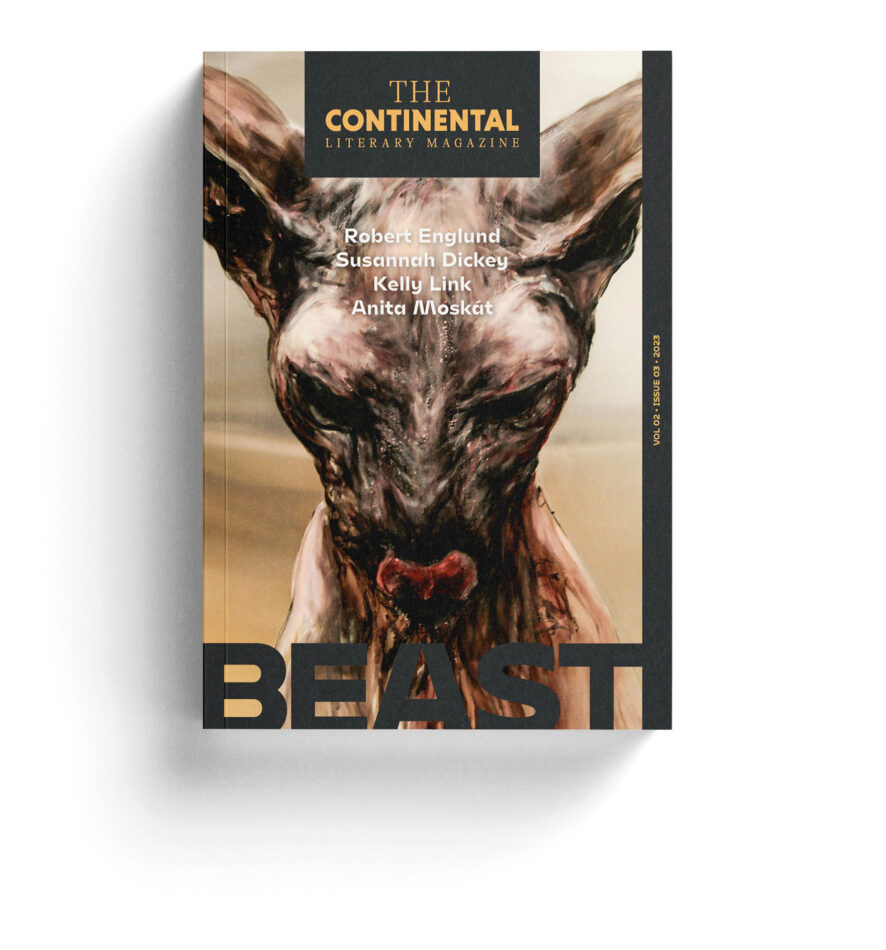

Beast comes from the Latin bestia. In Hungarian, the ancient term exists in the same form, however, the loanword has an interesting connotation: bestia can often refer specifically to a woman. Hence we chose a female Hungarian artist as the illustrator of the current issue, in whose pictures we can see women, and themes relating to women. Ágnes Verebics, visual artist and photographer, explores a wide range of bestial behaviour. We can see the female sexual predator, the cougar, and the maneater, while the sharp claws, pointed incisors, and nudity are reminiscent of witchcraft. Witches in many cases were harmless village healers with an extraordinary knowledge of medicinal plants. They lived in harmony with nature, with Gaia, unlike us in modernity, who, succumbed to our illusion of superiority, began terrible processes and swept the human race to the brink of a climate catastrophe. The bald cat staring back at us from the cover is our own stripped-down monster – Killer BOB snarling back at Agent Cooper in the cracked and bloody mirror, the serial killer who was such a good neighbour. Beneath the cute, soft, purring exterior of our civility, a ruthless sphinx lies in waiting.