5th April 2022

Interview

8 minutes read

Democracy Has Become Perverse

5th April 2022

8 minutes read

Interview Marina Abramović

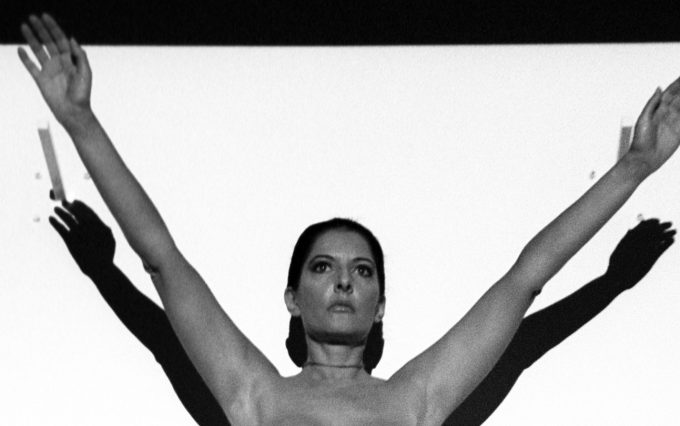

On a cold winter morning in the midst of new precautionary lockdowns and new waves of new COVID variants, internationally famous conceptual and performance artist Marina Abramović was kind enough to set aside an hour or so to speak with me on Zoom about her work and her ideas on an array of issues, including cravings for truth in modern times, death, silence, and her visions of her legacy. Abramović is perhaps the single most recognizable performance artist of our time, and indeed she is arguably the artist who has done the most to make performance art the vibrant, provocative form of art that it is today. It was generous of her to suffer through the at times wearying task, all too everyday for many of us now, of taking part in an interview online, and I would like to take this chance to extend my personal thanks to her for having given us the opportunity to include her reflections in this issue.

Dániel Levente Pál: Marina, thank you very much for accepting our invitation. As you may know, The Continental Literary Magazine is a new literary quarterly with a focus on Central European literature and arts. It is an honor to have you here with us, both because you are one of the most discerning artists of our time and because you have roots in the region. Our current issue revolves around the theme of “cravings.” What do people crave in our times? What is your definition of “crave”?

Marina Abramović: That is a very broad question, and there are so many different things that a human being can crave. I fear I run the risk of generalizing, so I will only speak on a personal level about what I crave as an artist and a human being. I crave truth. This is important, because I have always found that, in many ways in political society, given the way the news goes, the truth is hidden from us. We do not see the truth. Or we learn of it not when it is happening, but much later. Sometimes in history, we need 50 or more years to figure out that the news we were given was a lie. And then we look for the truth.

For me, the craving for truth is a very important thing.

The truth about everything, about relationships, politics, the universe, science, scientific discoveries, everything.

D. L. P.: Has this changed since you began your career or since the fall of the communist parties and the communist regimes in Central Europe?

M. A.: That is an interesting question, because when I lived in Tito’s time and before I left Yugoslavia, yes, in a way, the truth was hidden from us, but at the same time, we knew how to break laws. It was very clear. We knew that we would get four years in prison for a political joke. And we knew we would get six years for a political joke involving President Tito. There were clear rules concerning when you could take a dangerous step and make a mistake. As for the rest, everyone knew that politics was one thing and that what the newspapers were telling us was highly controlled, but we learned, at least in my country, to read between the lines. We learned that when there were long breaks when nothing was said, we had to interpret these moments and look for the truth, and we knew how to interpret them.

Also, history was completely rewritten. My mother ran the Museum of Art and the Revolution in Belgrade. And there were huge photographs of Tito with the politicians. Every time someone was removed from a position of political power but there was not enough money to have a new picture made with a new combination of people, they would just retouch the images, and instead of the person who had figured in the picture before, they would put a palm tree in the picture. You ended up with three photographs. You would have ten people on the original photograph and then a second photograph with one palm tree and a third one with three palm trees, for instance.

But at the same time, somehow everything was so clear. And then you come to the democratic countries. Now, I live in America, where things, I think, are so much more perverse, because things are distorted in complex ways in the name of democracy, and this is not truth either.

So somehow democracy can sometimes seem perverse to me.

D. L. P.: Last year, you spoke with the Indian performance artist Nikhil Chopra online, and the main topic of your conversation was the pandemic and the lockdowns. You said, “the one thing that I miss terribly, that I have seen completely disappear, is humor. There is no humor.” Your answer may have come as a surprise to some. Humor is perhaps not the first thing that comes to mind when one thinks of your image as an artist or your body of work. What is Marina Abramović’s take on humor? What kind of humor do you like?

M. A.: My work is always so serious, so demanding, both physically and mentally, that after doing the long performances, I need to laugh. I need humor, I need time to relax. And I come from an Eastern European country. But humor is important in the most difficult situations in our life, in times of war, of restrictions. Humor is how we survive. And not just innocent humor. Humor can also be dark or politically incorrect.

We had a writers’ club in Belgrade. There were microphones under the tables for the secret police, because writers can tell the worst jokes ever, but there are bits of truth in them. The writers knew that there were microphones under the table, but they would tell the jokes anyway. And they had to take responsibility for having told them, but this was the way to survive. When you are in difficult situations, when you really have to show emotional, political, and physical restraint, humor is the only way out. And that is important. And my work has to be balanced by humor.

D. L. P.: What do you think about political correctness? What effect does political correctness have on the arts, globally or in the US?

M. A.: I think political correctness has had a stifling effect on creativity. If you think about artists like the Futurists in the 1920s and 1930s, Dadaism, Surrealism, natural art, conceptual art, or performance art from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, these people had incredible freedom of expression and the freedom to express their ideas. The things that were done at those times constituted a major chapter in the history of art, but some of them would be not possible today because of political correctness.

Political correctness is damaging creativity, at least in my view.

Artists have to be free human beings. They have to have the complete freedom to express their ideas with no restrictions.

D. L. P.: Does political correctness mean restrictions on liberty?

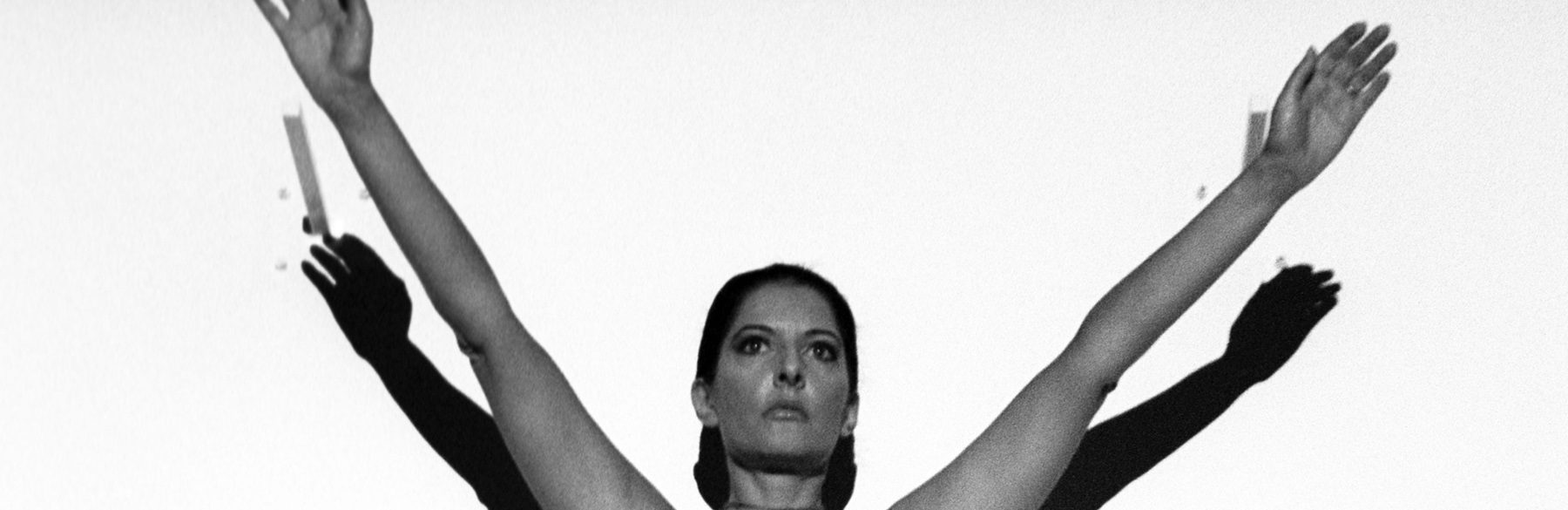

M. A.: You go to a museum and there are so many restrictions. I remember a piece I did entitled Luminosity in Berlin. I was sitting on a bicycle seat high on a wall, naked, in a very difficult position, for six hours. This was a work that did not have any safety fittings, no safety belts or anything like that. Then I was going to perform the work again. I wanted to re-perform it with a young artist in MoMA. Three lawyers came to discuss questions of liability and safety. They said that any given performance could only last 15 minutes. That was the maximum length, and they said that people would have to wear helmets. There was also an age restriction because of the nudity. I had to sign a form accepting responsibility, if anything were to happen, for a sum of up to one million dollars. I refused to wear a helmet and refused to use safety belts because they were ridiculous. I signed the form indicating that I accepted responsibility. I had to sign so many liability forms drawn up by lawyers that if anything had happened, I would be bankrupt now. But I signed them, I did not care. But it was incredible. It meant changing the work completely. And this was after I had already done the performance in Berlin for six hours, and there had not been any problems. Whatever risks there may have been, they were my responsibility, as it was my body that was part of the work.

FULL VERSION AVAILABLE IN THE PRINT EDITION.