19th July 2022

Non-Fiction

5 minutes read

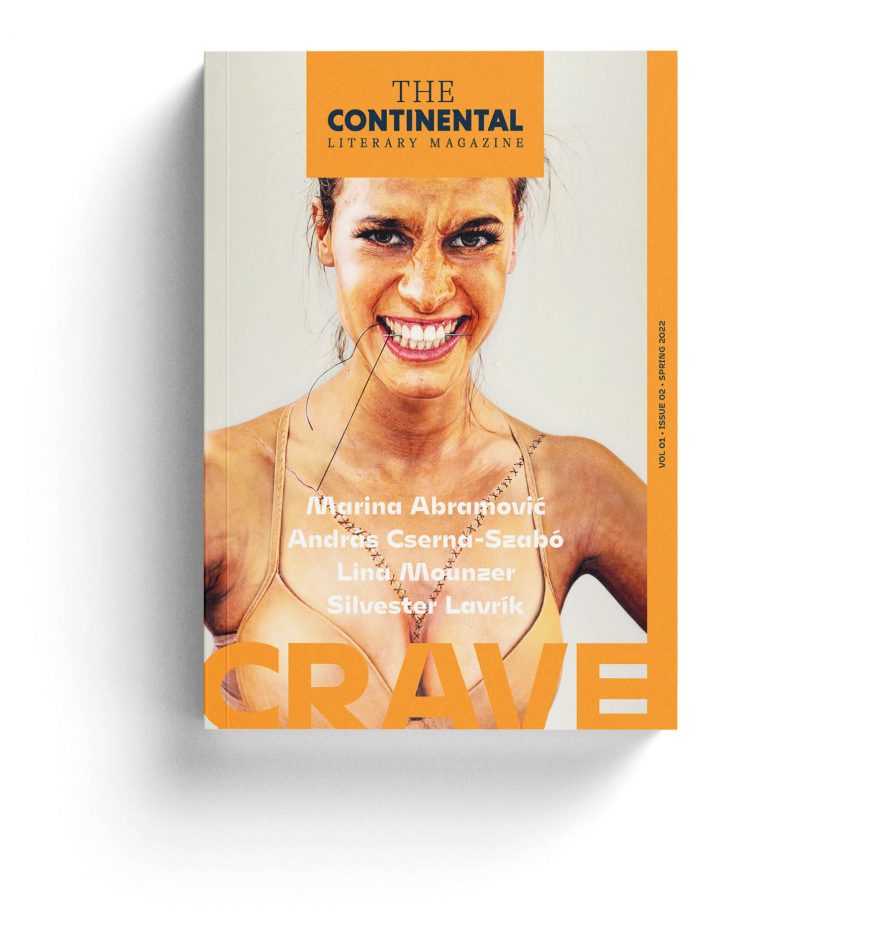

Room of My Own

19th July 2022

5 minutes read

How do violent conflicts over the possession of spaces transform the world in which an artist creates? Lina Mounzer ponders these questions as she writes about the tragic irony of a craving for a past that can seem inviting only against the backdrop of the present.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a woman in possession of artistic ambition must be in need of a room of her own. It doesn’t have to be a big room, or a room at all. Maybe just a quiet corner somewhere; a desk; a proper surface upon which to work.

In my old apartment, this was the kitchen, on the plastic picnic table covered with an oilcloth and placed next to the window.

But what a window!

It overlooked the one (tiny) public park in all West Beirut: Sanayeh Garden, renamed the René Mouawad Garden (though no one refers to it as such) after a private enterprise took it upon themselves to renovate it and repave its broken paths and its busted fountain (and then, upon its reopening, post security guards to make sure no one sat on the grass or played with a ball inside). Still, I was one of the privileged few non-rich in the city who got to look out of my window and see not walls but an expanse of green. Of trees. A lush Mediterranean landscape of pine, palm, willow, mimosa, frangipani, jacaranda, and oleander lining the paths of the garden and, right in the middle, a circle of ficus trees, their canopies grown and sculpted to join together in one continuous cover of deep, cooling green encircling the huge fountain. Beyond the garden were the charming red-tiled roofs of the national library (always on the verge of opening, but never opening) and beyond that, far off in the distance, was a small sliver of blue: the sea. Even when you were in the interior of the house, the day-long symphony of birds, rising to a crescendo at dawn and sunset, kept the view always vivid in your mind’s eye. Any new visitor to the apartment was offered a tour of the place, and, upon their acquiescence, was led down the hall into the kitchen and directed to marvel at this view as though it were a valuable piece of furniture I had proudly purchased with my own earnings or a room I had beautifully decorated with my own hand. The pride of the home.

Lurking right below the kitchen window was a parking lot. Everyone knows that in Beirut, a parking lot is a ticking time bomb. In the days of the war, this was almost a literal thing, as car bombs were one of the weapons the various militias used to terrorize enemy neighborhoods, and it was always easiest to disguise a booby-trapped car among all the other cars waiting overnight for their owners to start them up in the morning. After the war, they became ticking time bombs of another sort: empty lots always on the verge of being dug up to give birth to a new building. There were so many new buildings across the city that most of them sat half-empty, but even so, it was clearly business lucrative enough for them just to keep going up and up and up. The skyline was slashed with yellow cranes as far as the eye could see and the streets below torn up so fast and so thoroughly it was hard even to remember what beloved old landmark to mourn. And so it was pretty much guaranteed that any non-rich in the possession of a beautiful view accidentally furnished by the presence of a parking lot would soon find that oversight rectified. It seemed an affront to the moneymakers of the world: that someone might enjoy any kind of comfort or ease they hadn’t been made to pay for dearly.

But as I sat there at my kitchen table every morning, now tapping out a few words on my keyboard, now looking out at the trees, red roofs, and open skies, I had other things on my mind. Though I knew that the parking lot had been sold to a developer long-ago, there had been so many years of hearing “any day now” about when the ground would break on the construction project that it became like so much else in the country:

a possibility so postponed it had entered the realm of the impossible.

“Any day now” we’d have 24 hours of electricity instead of daily rolling three-hour cuts. “Any day now” we’d have proper Internet; a solution to the garbage crisis; a livable minimum wage; updated citizenship laws; a national library; a president. There had been months and months of parliamentary meetings to decide on a new president, all of which had ended in deadlock. Outside, everything was stagnation, but inside I was finally raring to write, now that I had found a place from which to do it.

My partner and I were both freelancers working from home out of that one-bedroom apartment, and he had immediately claimed the dining room table for his own. I tried working on the opposite side of the room, in the living area, but the desk that fit there was too narrow, and the distraction of having him—and his constant interruptions—there too great. I tried working in the bedroom, but it was far too cramped for any kind of desk, and working on the bed hurt my back and my ability to stay awake.

I tried working on the balcony, but the weather always had other ideas.

We were entirely too non-rich to afford renting a separate office space or even a desk in a coworking space, and the nearby library was one in name only. A friend of mine offered a room in her own office—but only when it wasn’t being used for meetings.