31st January 2023

Non-Fiction

6 minutes read

Wanted!

31st January 2023

6 minutes read

The Mysterious Absence of Eastern European Noir

We might as well put up a “Wanted!” sign looking for any traces of noir in Eastern Europe, in any shape or form – says I, who penned the, so far, only Hungarian noir novel, and one which is not so noir when it comes down to it.

It’s not “The Case of the Missing Noir,” rather it’s “The Case of the Noir That Never Was.”

Before going into details, I will supply a very short explanation for this absence: where there’s tyranny, there’s no freedom, and where there’s no freedom, there cannot be noir. (I borrowed and rephrased the line from the Hungarian poet Gyula Illyés’s emblematic poem, “A Sentence on Tyranny,” which will be relevant – even in the case of noir – until the end of times.)

For a longer explanation, I’d have to dig deeper into the history of Hungary and Eastern Europe. Before I do that, let me clarify an issue for all of us who use the term “noir”. Noir, nowadays, is more an umbrella term, and while many books have a swell time under this parasol, very few have a legitimate claim to be there.

In a broader sense, noir applies to crime novels and movies that show the dark side of crime. In a more restricted sense, noir is a story about morally corrupt people in which there are no heroes. Most noir novels don’t even feature a detective, or if they do, he is as morally bankrupt as his subjects. Noir shows people who have reached the end of their rope, or shows – in glorious B&W – the way people reach the end of their rope and hit rock bottom. Noir has no morals. Noir is about crime in its purest, ugliest form. So, for noir to exist, there has to be crime, that much is clear.

And here is precisely where noir’s entry into Hungarian and Eastern European culture was derailed.

When noir claimed its rightful place amongst the genres of crime fiction in the 1950s, Hungary was suffering under an especially clever and cruel tyrant named Mátyás Rákosi. He considered himself Stalin’s best pupil, and he did all he could to prove his aptitude to his master. So much so that Moscow reportedly was simultaneously repelled and surprised by Rákosi’s sheer brutality.

His credo was simple: where there’s socialism, there’s no crime. His subjects, us Hungarians, learned very quickly that punishment oftentimes comes without a crime, so only a very select few of our countrymen decided to commit crimes anyway. Those were such dark times that even the French cinema would have shied away from them. There were some petty crimes committed on a daily basis but those were handled by the authorities as direct and vicious assaults against the socialist system – meaning the people themselves. Naturally, murders were committed but those, argued the officials, were isolated incidents, and the killers were lone madmen, remnants of a bygone era (the Horthy-era of the pre-war period), or agents of the West.

To make matters worse, there was one slice of society that had a blank check to commit any crime they wanted to. Those privileged ones were members of law enforcement agencies, especially members of ÁVH (State Protection Authority). While David Goodis, Jim Thompson, and Charles Willeford freely published outstanding novels about social outcasts who had nothing to lose, Hungarian (and Czech, Romanian, Polish, etc.) citizens woke up every day without knowing whether by the end of the day they would still be free to sleep in their own bed, or would face a harsh sentence for a crime they did not commit.

This political climate only grudgingly tolerated the presence of popular fiction.

Even jazz was not accepted: it was labeled Western poison.

The novels published at the time tried desperately to avoid any topic that might show everyday struggles. No suffering was allowed in the wonderful socialist utopia, not even in fiction. As a result, these works were hardly readable. Even pre-war popular novels were banned and culled from libraries.

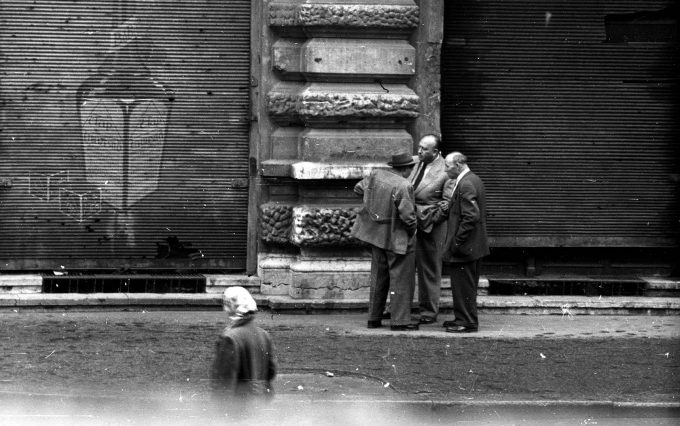

If there was nobody to commit a crime, except for the authorities, and there was nobody to write about those crimes, how could noir have been born in Hungary or the Eastern Bloc? The answer is simple: crime fiction, noir, mystery, and suspense novels were nonexistent for long decades in Hungary. This is a real pity since everything was set for the perfect noir novel and movie. Every proper noir has two main protagonists. One is the guy we read about, and another one is the setting, preferably a big city like New York or Philadelphia, or some hole in the ground in Texas, in Jim Thompson’s case.

Without a living, breathing location, the crime itself cannot be properly understood. The city provides the background and the explanation for the crime and the criminal. No crime stands alone, no crime is committed in a vacuum. Budapest was the perfect setting for a proper noir. Even today, almost 80 years after WWII, bullet holes still can be seen on the buildings’ facades right in the heart of the city. It was worse in the 60s. Even worse in the 50s. The city was filled with dark alleys, dangerous corners, and ugly pubs. And these places were never empty. The crimes committed there were interconnected in more than one way.

The great noir authors write about three types of crime in the genre’s rich, overheated environment. Crimes of passion, crimes of opportunity, and crimes of deliberation. The common theme is that the people who commit these crimes (somehow I’m reluctant to call them criminals, I rather tend to see them as victims of circumstance) don’t even see the distinguishing lines between these three types.

Back then, there was not much to steal.

Whatever was left after the total devastation of WWII, was taken away by the state after 1947, and whatever was left after that, was hidden – or sold to make ends meet. Hungary was as poor as they come. Sure, theft and robbery were present, but the trophy was usually a coat or a bicycle or an empty purse. And since private property was frowned upon, and valuables were owned and controlled by the state or its minions, any crime against property of real value was a crime against the state.

FULL VERSION AVAILABLE IN THE PRINT EDITION