23rd March 2023

Non-Fiction

13 minutes read

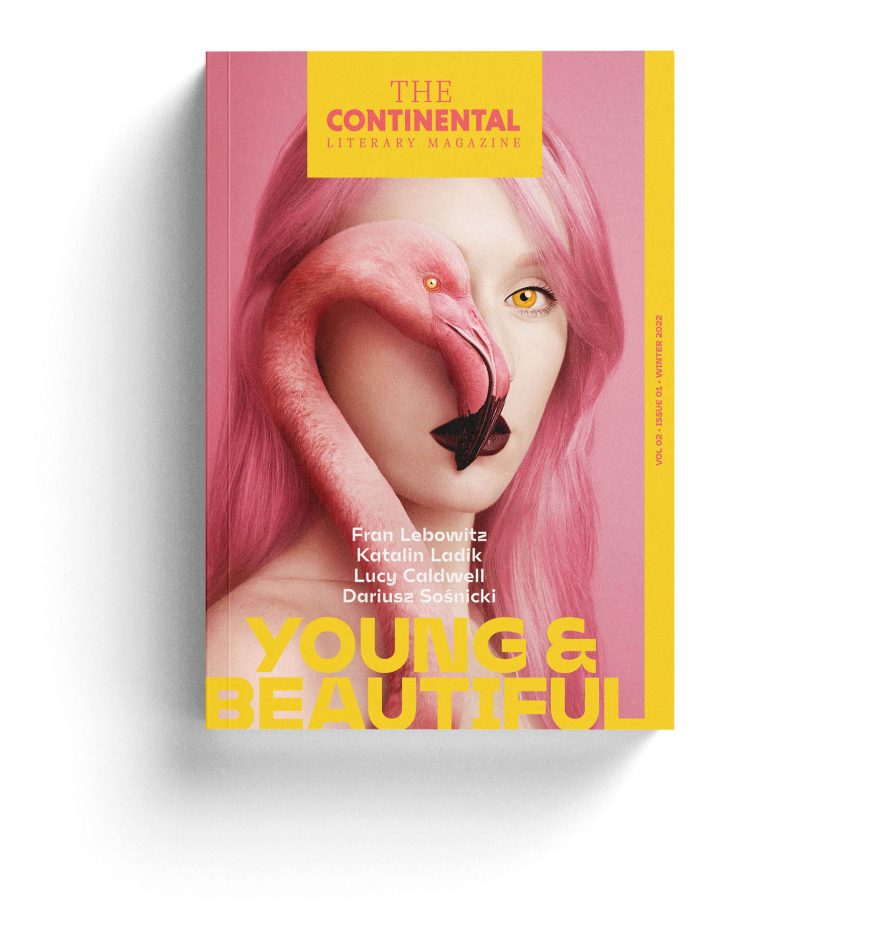

Some of the Beauty is Still in Me

translated by Mascha Dabić

23rd March 2023

13 minutes read

Young and beautiful – I used to be that too, but I was not aware of it, back then. In the meantime, someone helped me to learn to spot my youth and beauty in old pictures. However, at that time, when I was young, I wasn’t even supposed to see that beauty of mine, because I thought that beautiful people were highly superficial – this was especially true for men. In those days you couldn’t call someone worse names than “pretty boy”.

If an intellectual was beautiful and young too, he was discredited anyway – nobody would take him seriously.

And even more so if he knew how to dress well. In that case you would think that all he wanted was to impress other people with his good looks.

It took me a long time to realise that actually I had fallen for a cliché of the German-speaking world. In Romance countries, writers and intellectuals can be good-looking, and no one would think of doubting their intellectual skills for that reason. But in German-speaking countries someone like Albert Camus, who so suspiciously looked like Humphrey Bogart, would probably have never been that successful, because of his good looks, of all things. In our country, serious writers and intellectuals had to look as ragged as possible and it was considered impossible for them to have a good haircut. So even if they were good-looking, they had to hide it somehow. Also, when I was young, you had to smoke as much as possible, if you wanted to be perceived as an intellectual. And I did want to be, or at least to become an intellectual. How could I have been a good-looking young man then? I could not have looked at myself in the mirror if I had thought of myself as young and beautiful.

But anyway, the risk of me feeling beautiful was not very high because there was still the fat child lurking inside me, the one who had been called “Mammoth” by other kids in the first few years of the grammar school; another name that I was called was “spectacled cobra” because the glasses that I wore were of the cheapest kind and looked just horrible, but back then we couldn’t afford any better. And I wasn’t well dressed either. I used to wear the so-called “high-water trousers” that were always too short, because I had outgrown them. It was obvious that I was wearing such trousers because in my teenage years I would grow quickly and we did not have enough money to buy new trousers several times during one year.

But actually, when I was in school it was not that bad to be visibly poor and not so good-looking.

For Jesus had special love for the poor – certainly much more than for the young and beautiful,

who were bound to cause displeasure to him, the poor preacher and suffering Saviour; the ugly ones were closer to him. And I wanted to be especially close to him, because I went to a Catholic school and had long wanted to become a priest. Being young and beautiful would only have been an obstacle, because a Catholic priest has to stay away from women. But for everyone else, too, there was always danger coming from the body, as the body was the source of sin.

When I was studying Theology (yes, I actually studied Catholic Theology, among other things) I got familiar with the concept of the Apostle Paul, for whom “soma” (body) had a negative connotation. True, he was not the one to invent this kind of devaluation of the body, it was just in line with the culture of his time. But it was due to his efforts that this concept had a lasting impact in Christianity. And then, Paul loved the word “sarx” (flesh), which stands for affects and aggression and is opposed to the Spirit of God. Without God, you can’t get out of the mess of your body.

It was much later that I read Albert Camus. I felt, his texts put the Christian devaluation of the beautiful body (and the glorification of the martyred body) into perspective. In 1941 he wrote an entry in his notebook under the heading “For a generous psychology”: “For two thousand years man has been offered a humiliating image of himself. The result is obvious. Anyway, who can say what we should be if those twenty centuries had clung to the ancient ideal with its beautiful human face.” It may well be that Camus is romanticising antiquity here, to a certain extent. But he is certainly right when he is criticising Christianity. And yet he does not glorify the body either. In another entry in his notebook he focuses on the ambiguity of the body and writes, obviously aiming at Paul: “The flesh, the poor flesh, miserable, dirty, faded, humiliated. The sacred flesh.”

It dawned on me only slowly that the body and the experiences attached to it could be something unique or, in the language of religion, something sacred – in special moments that have burned themselves into my body’s memory and can never be erased. However, for a long time I did not even dare to consider myself young and beautiful. When in my student days a young woman I knew – she worked in a travel agency, was always tanned and dressed in the latest fashion – told me that I would have no problem winning over any woman I wanted. I was euphoric about her compliment, but at the same time I was suspicious of her words:

A woman I could win over because of my looks could only be a superficial woman.

At that time, I was already feeling the crumbling of the Catholic framework of thought and feeling, which was centred on the body that was always prone to sin. Instead, the mission of being an intellectual became all the more decisive in my thinking. An intellectual should deal with thoughts only and not make any effort in order to optimise his body, so of course a true intellectual should not be sporty. I would distrust a professor who gave the impression of rushing off for skiing holidays, and perhaps so even in the middle of the semester; I didn’t want to take a seminar with such a person. So when I was young, I didn’t even allow myself to feel the desire to be beautiful. And that’s why I didn’t see myself as beautiful either. Only as young.