4th April 2023

Interview

11 minutes read

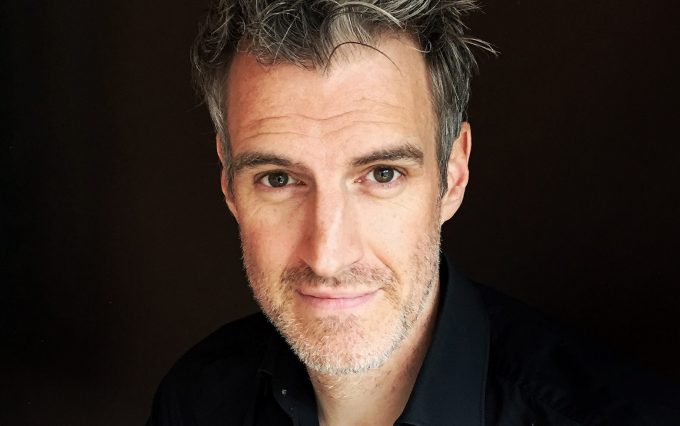

Gloom for Laughter

4th April 2023

11 minutes read

A conversation with crime writer Thomas Raab about the origins of mean-spirited Austrian humor, the ability to stumble and laugh at oneself, and the hopeless search for the ultimate answer.

Márton Méhes (MM): Mr. Raab, what comes to mind when you hear the term “noir”? What works, authors, or films? Where do your thoughts stray when you hear this term?

Thomas Raab (TR): Perhaps I would think first of my back wall (he points at the wall behind him, which is pitch black). It’s a chalkboard wall that I use when I want to write down keywords. I highly recommend black. This is my study: I work in the basement. Very Austrian, I would say…

Certainly several films would come to mind. I recently watched the first season of True Detective on Sky. You can’t get more noir than that. It’s a gritty mini-crime series. Another recent example is the series Mare of East Town with Kate Winslet. Dark but also warmhearted.

In literature, for me, noir is never without humor.

Everything that comes to me in terms of noir when I’m writing makes me laugh first. A scene comes to mind with Metzger, a character from my novel, that takes place in a hospital. Metzger looks out the window and suddenly sees a handbag tumbling down. As I write cinematically, I immediately have a laughing fit, because I imagine that someone is going to come tumbling down after it. And indeed a woman does come flying down, right past the window, and I can’t help but laugh. I don’t find it tragic, I find it insanely funny! And out of this comes what is called the dark-humored Austrian crime story. You can’t make it up. It just happens, it happens in me, deep inside me. I can’t explain why. It’s the Austrian soul. The Austrian component that distinguishes the Austrian crime story from areas where other languages are spoken: a dark-humored crime story which bears the Austrian genes.

This “Austrian Schmäh,” or Austrian blarney, is often referred to as cultural heritage, but in truth, it is one of the darkest characteristics of the Austrian. In truth, it is a barefaced lie. An Austrian who uses “Schmäh” lies to his counterpart’s face while wearing a friendly smile.

MM: Schmäh leads into the depths of the Austrian soul… Meaning that cynicism and dark humor are understood and “practiced” all over Central and Eastern Europe. Why are we like this?

TR: This question is a bit dangerous, since fundamentally every person is different. Nevertheless, one can clearly recognize an Austrian tone in my inner attitude. As if the tendency to see, write, and think in this way were in our genes. I am convinced that mental attitudes and experiences that were perhaps never told to us are nonetheless passed on.

I remember my grandfather, who returned from the war in the east, from Russian captivity. He sat in his yard and puffed on his pipe. Never uttering a word. As a child, I sat in his lap. I can still smell him, but I can’t remember his voice because he never really spoke. What crimes did he learn to live with? And I think of my father, who was also taciturn and strict, and of how he must have born the brunt of this. My father was a Catholic priest before he met my mother.

Many, many things left unsaid that led to me becoming part of a generation of parents who talk and talk and talk.

It’s all closely interrelated. I think one can say that this is what the Austrian is like. An Austrian thinks like this and writes like this.

MM: What we all carry inside us and with us may be an important explanation for the distinctive Austrian attitude and regional attitude, but it is not funny in and of itself. Where does the humor come from?

TR: I rather suspect that, globally speaking, the smallness we carry within us, which also applies to Hungary and the neighboring states, invites us to pull ourselves up, stride through a big doorway, and then laugh at how much room we still have left. If, as a dwarf, I were to feel worse about myself every time the giants around me were laughing at me then I might as well simply dig my own grave or shoot myself. But if I can laugh at myself and at the same time hold a mirror up to others in which they can see their own haughtiness, that’s an adequate solution to make one’s way through life. I believe that this Austrian “Schmäh,” the disingenuousness and meanness, originally comes from this constant feeling of smallness.

I played as an extra for a long time at the Vienna State Opera. In the triumphal procession scene in Aida, the soldiers march forward to the stage, row after row. One time, one of the extras dropped out. The replacement was made the victim of a prank and was given a random costume that didn’t fit him: he was too short for the long coat. As we marched out onto the stage, with every step, he put his foot on his garb and got smaller and smaller. He couldn’t remain standing and went down on his knees at the front edge of the stage like a puppet and fell. In the middle of the performance. A wave of laughter went through the hall, and he laughed too. We all laughed. Austria is a bit like that! It’s small, and it stands on its own cloak, falls down, and laughs. And everybody laughs. But this laughter makes the person who has fallen down taller! People are laughing at him, but he is laughing with them. This creates a sense of admiration and elevates him above his fate. This is perhaps the explanation I can offer for the grim, dark-humored Austrian soul.

MM: Gloom and meanness as parts of an intangible cultural heritage sound frightening on the one hand, but on the other hand, these qualities enrich the melancholic-cynical noir and crime tradition, which has recently become so famous. Is the gloomy side of the Austrian a good thing for literature?

TR: Yes, I think it is! Wolf Haas was perhaps the only one who really managed to hit it big. Austria owes him a lot. He spent ages looking for a publisher and was turned down over and over again, but in the end, he found a sanctuary, and then he suddenly became successful. From then on, publishers paid more attention to the offbeat, the absurd, to writing styles that could not be precisely described in literary terms. That was what they were looking for. Without Wolf Haas, neither Stefan Slupetzky nor I would exist.

What is beautiful in this literature is that it cannot be pigeonholed, and this is also a problem for our trade.

The book of life is perhaps not a crime novel or a romance novel, but rather a combination of all of them.

MM: From the point of view of the use of language, your texts are a delight. But the rural-provincial social milieu that you portray is also fascinating. I recently traveled across Upper Austria. I was in the middle of your novel Walter muss weg, and over and over again I had the impression that I was running into characters from your novel. Someone from the village of “Glaubenthal” (the fictional but very realistic setting of the novel, which could be translated into English as “Faithsdale”) was constantly coming up to me.

TR: Oh, I’m very pleased to hear that! (He laughs.)

MM: Though at the same time, I was wondering what happens when these people from the rural areas read your book… do they read it at all? And when they read it, do you sometimes get reactions? Are the descriptions of this world sometimes taken as mockery or cynicism?

TR: Not at all, on the contrary! I have given readings from Walter muss weg in many small towns in Germany. After the readings, people everywhere wanted to tell me about the characters in their villages who were exactly like some character in my novel. And they all saw someone else in these characters, never themselves! It brings me joy!

My father is from Upper Austria, and as a city kid, I spent a lot of time in rural areas. I was thus able to draw on my own experiences. That includes the experiences I gathered when I traveled to do readings. I’ve noticed that it’s traveling and being among people that defines me as a writer. To be a writer without being among others is hard for me.

MM: To return to the topic of “crime fiction,” one need merely take a glance at the television programming or the spines of the books on the shelves in a bookstore. Crime stories are everywhere. They are more popular than ever. Why is that?

TR: The primal nature of humankind is curiosity, which has led us through bitter times but has also revealed a great deal. Humankind is always looking for answers, perhaps in part because we are doomed hopefully never to be able to learn the answer to the most important question: what waits for us at the end of our lives? Like Sisyphus, we try to keep ourselves above water with solutions that we believe can explain the world to us, though we can never explain it to ourselves. The crime story is one of the best ways of doing this. At the beginning of the few hundred pages, you find a question, a riddle, and you can spend the whole time looking for the solution. At the end, you know what happened. You close the book and say: now I know my way around. It’s like when you fill in the last number in a Sudoku puzzle and say, “I did it!”

MM: The crime story as a substitute for the ultimate answer. But at least you figure out the next murder, so there’s one less riddle at the end.

TR: Yes, but greatly simplified, because the crime story brings death to a simpler level. One believes to have clarified a partial aspect of this question that can never be solved.

MM: Some claim that noir or crime fiction is a masculine genre. What do you think? Is noir somehow a male domain?

TR:

Well, Agatha Christie achieved a thing or two, didn’t she…

But what one really sees very clearly lately is that many prominent positions in publishing in the German-speaking world are occupied by women. There are many examples at Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Piper, Droehmer. We’re coming out of this male-publisher world that was responsible for the fact that, until not so long ago, the literary world was also male-dominated. When you read the German author Tatjana Kruse, you realize that it doesn’t really get any more dark-humored and darkly funny than this. There are still perhaps too few female writers who have been able to fight against the current and present themselves in a world which we have tended to think of as primarily male, but in 50 years, we will probably be speaking about all this very differently.

MM: Publishing houses, producers, the whole film and TV industry… all male-dominated for decades, but bit by bit, that’s changing.

TR: Yes, and now the whole industry is on guard, because for years, women cinematographers and directors were denied admission. In the meantime, attention is being paid to the balance in funding and in training and education, which I think is as it should be. I am convinced that women cinematographers and directors have a completely different approach when it comes to filming. They approach themes differently, and they work differently than men when it comes to work with groups. The industry is being punished for its arrogance. The same may be true in the world of literature.

MM: What can we look forward to from you next?

TR: My next novel, Peter kommt später, will be the third Huber case. It’s forthcoming in spring 2023 by Kiepenheuer & Witsch, and Haymon-Verlag is currently republishing my old Metzger novels. A very enjoyable project. New film adaptations of the Metzger series are also in the works. In the autumn of 2022, there will also be something completely new. I have been doing work with Austrian Cancer Aid on a project called “Mutmacher,” or “Boldmaker,” meeting with and doing interviews with twelve cancer patients. These were incredibly impressive encounters. Out of these conversations, a book is being written with Martina Löwe (Managing Director of Krebshilfe) which is intended to give courage to people struck by cancer (and the profits from which will go to Krebshilfe). This project already existed for women (https://mutmacherinnen.at). Now, it exists for men.

MM: Mr. Raab, many thanks for your time and for this conversation.