6th April 2023

Interview

27 minutes read

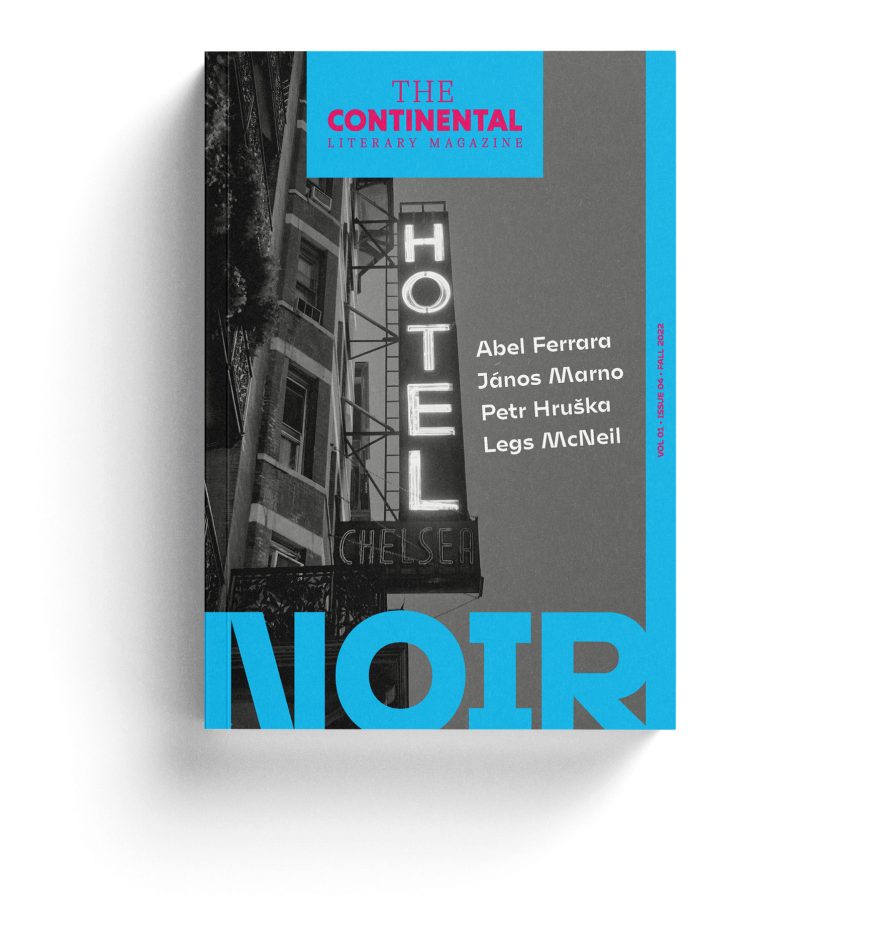

“It Was the Hotel that Picked Me” – an interview with Tony Notarberardino

6th April 2023

27 minutes read

Cover Image © COLIN MILLER

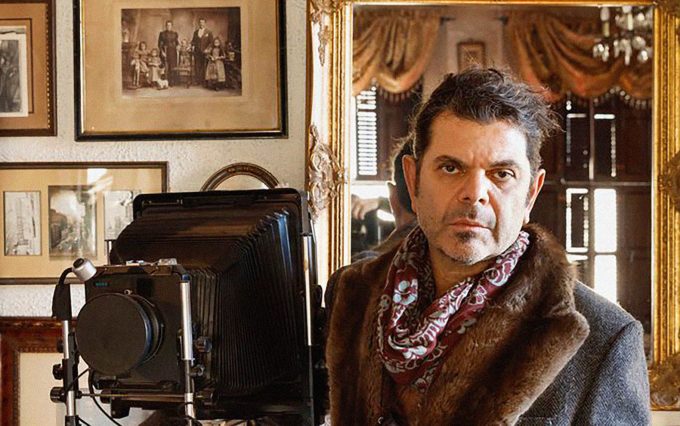

Photographer and cinematographer Tony Notarberardino has been a permanent resident of the iconic Chelsea Hotel in New York City. A chronicler with a camera, he has countless personal anecdotes from this legendary dim of artists and misfits, some including Arthur C. Clarke, Dee Dee Ramone, or Abel Ferrara. Tony’s pictures illustrated the Noir issue of our Magazine – this time we called him on Zoom to chat about the stories behind the images.

It’s noon in New York, but it looks as if it were nighttime there.

Yeah, you can even see the working fireplace here (turns the camera around to show his fireplace in the dimly lit room.) This building is like no other building. It’s got such a personality that it’s hard to explain. It’s the middle of the day, looks like nighttime. Not that time has such a great significance here. It’s just a unique world we created for ourselves.

How did you end up in the Chelsea Hotel?

I think it was the hotel that picked me. It was an unconscious decision. I was born in Melbourne, Australia, but I left when I was very young. I lived in Sydney and then I moved to Paris, where I lived for two years. I lived in Italy, London, and I always wanted to go to New York. I visited once and I just thought one day I’m going to live here. But this is way before I even came to the Chelsea Hotel. I was living in Sydney, and I packed up my life to come to New York. The history of the Chelsea didn’t enter my mind. I was coming to New York because that was my dream. It so happened that a friend of mine was living here. And he said to me “When you come to New York, come and stay with me for a few days until you work your situation out.” And I called him. That was ’94, so that was life before computers, life before smartphones… we called each other on landlines. I called one night to tell him I was coming and this woman answered and said in this very deep voice, “Hello, the Chelsea Hotel”. I hung up. I thought I had the wrong number. So then I dialed back and she again said, “Hello, Chelsea Hotel” and I said, “Oh, I don’t know if I got the right number. I’m looking for so-and-so.” And she put me straight through to his room. And that’s the first time I really thought about the Chelsea Hotel.

So how did you end up staying there?

My friend answered. I said, “Where are you living, man?” He said, “I’m living at the Chelsea Hotel.” I said, “What are you doing there? I mean, for starters, how do you afford to live in that Chelsea Hotel?” He said, “Look, it’s a long story. When you get here, I’ll explain it to you.” When people ask me, how do I live in the Chelsea? How do I afford to live in the Chelsea Hotel? It’s the same thing. It’s a long story. It’s a crazy kind of circumstances that brought me here. But back then it was different because the hotel was residential AND hotel. There had been tenants living here since the hotel opened. And so it wasn’t that unusual. It was unusual for me coming from somewhere else because where I came from, even in London, nobody lived in hotels. In New York many hotels had tenants. When I arrived here, I got my own apartment pretty much the same day because he was living in a room upstairs that was very small, and I needed space. I went downstairs and spoke to Stanley Bard, who was the owner at the time. And straight away said to me, I have a room I think you’re going to like. This was the magic of Stanley.

Could you tell us about him? What kind of manager was he?

Stanley ran the hotel for half a century. His father bought it in the 1920s.

Stanley grew up in the hotel, assumed the role of manager at some point in the forties and fifties, and managed it for the next 50 years. It was because of Stanley’s passion for art and artists. He was an old-fashioned Jewish landlord whose job was to run the hotel, but he had a real passion for artists. That’s why the hotel became what it was because he would help people and he would attract that kind of clientele. When he met me, it was almost like he just looked me up and down, didn’t ask me too much, too many questions. It was really early in the morning. He just arrived and he said, I think I have a room you’re going to like. He got the key, and he showed me, and we walked into this very room. And this was 1994, nearly 28 years ago. And I never left. And I’m still here in same room.

What made you remain there?

When I arrived to New York I had very little money to begin with. I had no creative background. It’s very hard to get an apartment in New York. Here they didn’t ask questions. You pay the rent and that’s it. It was easy in the beginning. I didn’t have to look for an apartment. It became obvious to me immediately that looking for apartments inNew York was tough and expensive. People thought I was crazy living here because at that time the hotel wasn’t what it became. Also, the area here in Chelsea was kind of dangerous. I didn’t know that much about New York. To me it was convenient, and I loved it. I immediately had a connection to the hotel. But I didn’t think I was going to stay this long. In fact, Stanley, when he gave me the key (in this very room), he turned to me, and he said: “you’re never going to leave here. You know that.” And I just went, okay, sure. But he said that to me because he knew that people get an attraction to this place…like you would fall in love with a person. It’s the same thing. It’s hard to explain.

What was it that attracted you to the place? How has it influenced your work?

I’m a photographer, so it didn’t take me long to realize that this place had a lot of interesting people. And it didn’t take long for me to meet them. I made the decision to start taking pictures of them. I was compelled to photograph and document the people I was meeting. It wasn’t an intentional project. I didn’t come to New York to live at the Chelsea Hotel nor to do a project here. The Chelsea Hotel Portraits was a reaction to the circumstance I found myself in. I kept saying it to myself, “I need to photograph these people, I need to photograph these people.” Until one day I said to myself: “Enough is enough, I’ve got to photograph now!” Let’s not work out too much about how to do it. Let’s just start doing it, you know?

I set up a camera here in my room and my intention was to focus on the people.

Because I’d seen a few books that were published, I’d seen a lot of stuff on the hotel by that stage. I wanted to focus on the people, not so much the hotel. I didn’t want to go outside and photograph the rooms and their inhabitants. I wanted to photograph the people themselves. So that’s when I made the decision to shoot them all in here before a neutral background. So that way it would become a study on the people.

Your pictures really give a cross-section of the Chelsea’s population.

Yeah, because I wasn’t picking people: I shot whoever I found. In the beginning, if I met somebody in the lobby, I would approach them and ask them or someone who would be checking into the hotel. That was interesting. People that lived here, people that worked here. Back then, there were many projects happening at the hotel. There were art shows, films were being made, all kinds of things. I’d wake up and walk out and there’s a big film crew out there and there’s Robert DeNiro all of a sudden standing outside in the hallway. It was like this every day. There was always incredible stuff going on. I didn’t have to find the people, they would just come to me. The project dictated itself by the people that came through here. There was no shortage of extraordinary people I found here.

And they came to you.

On a daily basis. So as an artist, I’m like: “Why would I want to go anywhere else? I mean, I’m going to leave here, and do what? Live in a flat in Brooklyn? I mean, this this became, like, such an amazing world I found myself in. It was a world of its own.

One can read a lot about the myth of the Chelsea Hotel. How does the reality you experienced differ from the myth?

Yeah, that’s a good question. I guess I lived through many situations that were the part of the myth. But you have to define what a myth is. The myth of the hotel was created and passed down in stories. The things that happened here over the past 50 years, it’s unbelievable. That’s the myth. As for the everyday living… I guess you need to break it down to the old Chelsea and what it is now.When I came here, Stanley Bard and his family (he had a son, David, his daughter Michelle) were managing the hotel. At that time Stanley was already in his late seventies, eighties. He kind of took a backseat and let his children do the business. Just like his father did in the 1940s, I guess. It was a family thing, but his children were very much in his style of management. They cared about artists. They wanted that community here. And they are smart business people …to have Leonard Cohen living here, it’s a good business decision, let’s face it (laughs). Then in 2010, the hotel was sold. It was a sad story. It was a real cultural shift for us because all of a sudden the hotel was closed. No guests. They started demolishing the hotel to rebuild. And that went on basically for the next 12 years. We’ve been enduring 12 years of living in this void. It was very strange. It was almost living in The Shining. It was very much like that for the first few years because the hotel sat empty and they didn’t start any construction, so everything was empty. For the six months, when they sold the hotel and all the tenants moved out and they closed all the rooms, I went into all of them and photographed the empty spaces. I have that as well, which I haven’t really shown to anyone. They just left them: unmade beds, even the food. The guests just left, then they closed the hotel and left it as it was. Incredible. That was a weird period. So it is really difficult to say what’s the difference between the myth and the reality of living here. Because back then, the myth and the reality was one. I don’t know the direction of the hotel now, apart from the fact that it’s expensive now and we are living in more of a boutique hotel. So the myth exists… somewhere else (laughs). The myth of the Chelsea is now just a myth. We are writing the next chapter of the hotel as we speak. It has been open now for a few months. Not all. They opened half the hotel. Who knows what’s going to happen? I don’t know. But the myth is what I remember of the Bard era. And that’s what I focused on and documented. My project pretty much is the end of an era.

Would you mind sharing some of the best stories you have in connection with the people you’ve met?

Well, a lot a lot of them revolved around my project, obviously. When I first moved in here, I was a shy person. New York was overwhelming. I got a feeling that people wanted to be left alone here. They didn’t want to be bothered. Until I started to explore, meet people that lived here and that opened a whole new world to me. In the beginning, it was hard for me to really open up. But the project forced me to really meet people here. It’s hard to say because every portrait to me is important, whether it’s Sam Shepard or Sam the cleaner. I find the same kind of power in the portrait.

But if I was to pick one of the most incredible people I’ve met, it would have to be Arthur C Clarke.

Who famously wrote…

Yeah, well, he wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey at the Chelsea in the 1960s. One day I got a phone call from Stanley. Back then he used to call us on the house line because we had phones in the hotel phone. The hotel phone rang, Stanley answered, and he’s like, “Tony, Tony, I need you to do me a favor.” I’m like, “Yes, Stanley, what?” And he was: “Arthur C Clarke is coming next week, I want you to take a picture of me and him outside the hotel.” And of course, my mind just started exploding. I said “Okay, Stanley, you’ve got to do me a favor in return. You can ask him if he’ll be do a portrait for me.” He said, “Tony, all I can do is make the introduction. It’s up to you to work it out.” The day came, Clarke arrived, and I found out that he was coming for the scientific convention here in New York. I think that’s when they were launching the Hubble telescope. See, a lot of the scientists grew up with his writing and idolized this person. A lot of the stuff he wrote about they made into fact, like satellite technology and other things he was writing about in the 1950s. So he was invited by this group of scientists that absolutely admired him. To them, he was like a god. Of course his choice was to stay here at the hotel. When he came, he stayed in a room here on the sixth floor. I’m also on the sixth floor, right down the hall.

He came with a bit of an entourage, there were people who looked after him, because he was quite old at that point, already in a wheelchair. And Stanley rang me and said, “Go meet Arthur tomorrow morning at 10:00 and then we’re going to come down after that. But we’re going to do a photograph downstairs in the lobby.” At 10:00 that morning, I went in and knocked on the door and this Sri Lankan man opened, because Clarke was living in Sri Lanka at the time. I walk in, and down the corridor there were five Sri Lankan guys, all standing there. One would cook for him, the other would look after him. I walked in the room and I never forget it. It was this beautiful big room. Full of antiques. And in the corner there was a desk near the window and there was an old man with his back to me looking at something on the desk. I froze for a moment, because it reminded me of that scene from 2001: A Space Odyssey. I think it’s one of the greatest cinematic cuts in history. There’s a scene in the movie where this kaleidoscope is going through the universe and then after all these colors all of a sudden it cuts to the inside of the spaceship. And it’s this old room with the floor, but the floor was plexi and had lights underneath it. Clarke’s room was the same without the floor. And there’s an old man sitting there in that scene. And I almost fled, but I was also shocked in the moment because I thought, wow, this is crazy. Because it’s one of my favorite movies. And that scene in particular. I went over there and there he was.