About the Issue

Future Devoured

Apocalypse or redemption. Annihilation or ascension. Elevated by modern technology, the descendants of western civilization see the future as being the fulfillment of one of these two extremes. Both the end of the world and its redemption are equally acceptable scenarios. Can a species that launches life-support systems into orbit, regulates rivers, or plans its diet with geometric precision according to the latest scientifically approved trends possibly be able to face the future’s unpredictability and the unknown? Not a chance. We believe the direction of our life and our future is in our hands, while knowing, deep down, that this is far from true. The unknown gives rise to anxiety in us, and we strive to dispel that anxiety with our extreme projections. Whether it’s the end of the world or the golden age: we called it. Anything can fit in between. When you prepare for the worst and the best, there are no surprises.

Here in Central Europe, over the last three years several things have become a palpable reality that we would have gladly seen only in the force majeure clause of a contract: intensifying and unpredictable natural disasters, a pandemic, and a war. The future is near. The future is now. Its approach is unstoppable: you can never halt development or the perpetual motion in which we find ourselves. We call on technology’s aid to better our quality of life, we are willing to break from our biological limitations and become superhumans. In a curious contradiction, we may well voluntarily become biorobots with the help of transhumanist tools, while at the same time we tirelessly strive to create the most human android possible. Sometimes trying too hard, take one look at Robert Zemeckis’ animated Christmas film The Polar Express for a perfect demonstration of the uncanny valley effect in all its glory. In The End of History and the Last Man Francis Fukuyama predicted the end of ideological development and the universal end of history but he must have been wrong. We are splitting our ideologies into subatomic particles at an ever-wilder pace, as the development of artificial intelligence slowly culminates in a technological singularity. In the shadow of undetectable changes our future models become unusable.

In spite of that, the future is an opportunity, a fate that must be fulfilled, and a threat painted rather too bright by the optimism of techno-modernism and rather too gloomy by climate anxiety. At such a time, the responsibility of literature and the arts becomes indisputable. In our FUTURE issue we are searching for the answer: can literature and art offer relevant visions of what awaits us?

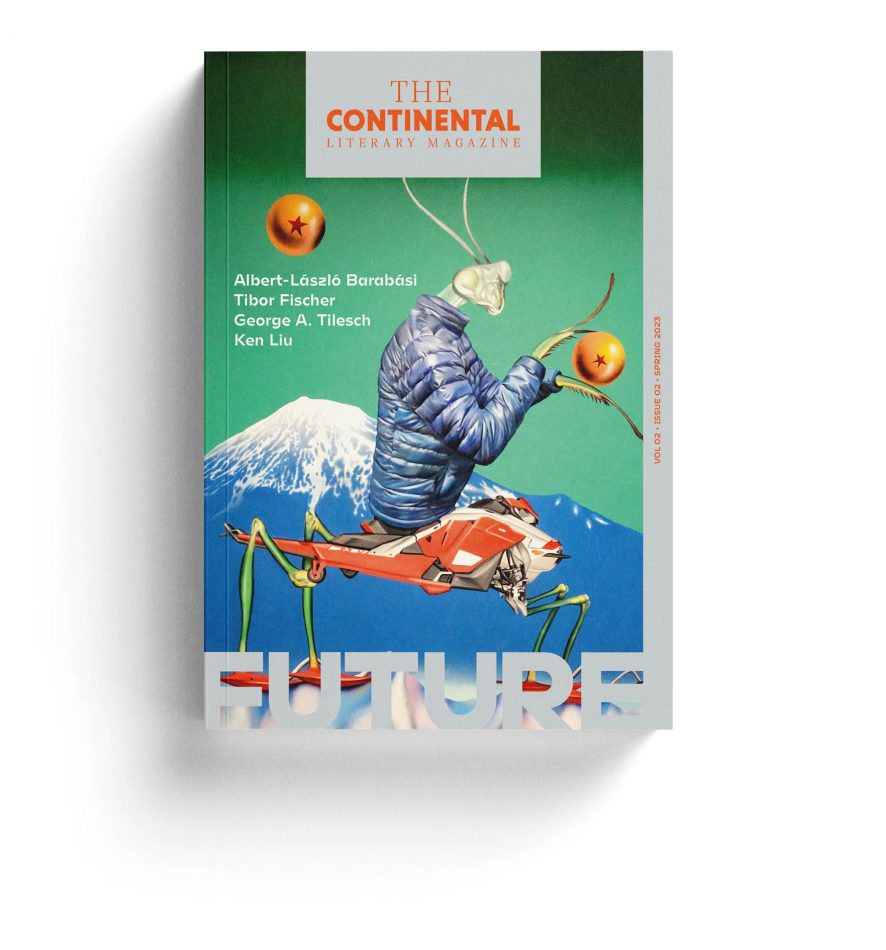

For the art section of this issue, we have selected from the work of Hungarian artist Botond Keresztesi. In the disturbing pictures by this young artist from Târgu Mureș, both past and future are present. Historia est magistra vitae, history is the teacher of life, said Cicero. Keresztesi searches for the answer to the future’s great questions in the myths of the past. Looking at his pictures we find sudden enlightenment and discover cyclicality. Like Denis Villeneuve’s giant octopi in Arrival who see the past and the future simultaneously, here a jacket-donning robot mantis, reminiscent of the locusts that plagued Egypt, presents us with a warning: we are devouring our future.

FROM THE ISSUE

What is the future of crypto, or rather, what is its present? Is it a revolution in the decentralization of power or a Ponzi scheme doomed to fail?