10th November 2021

Non-Fiction

5 minutes read

The Power of No: A Meditation on Boundaries and Black Womanhood

10th November 2021

5 minutes read

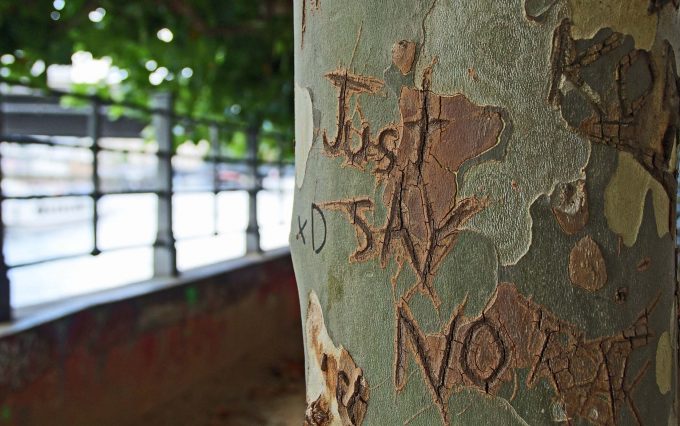

I am terrible at saying “No.” I’m too eager to please, or, more accurately, I am terrified of disappointing people. But it’s more than that. I rarely feel like I have a right to say “no.” And so I say yes to nearly everything or I say nothing and people interpret my silence as consent.

When tennis player Naomi Osaka told journalists at the French Open that she wouldn’t be doing any press, the outcry was passionate.

Tournament officials made not so subtle digs at the number two player in the world. Some fans expressed support, while others expressed disappointment. Some journalists acknowledged that sports journalism can be toxic, while others proclaimed that doing press is part of the job. Some lip service was paid to the importance of mental health and addressing depression. In the end, there was so much scrutiny that Osaka withdrew from the tournament entirely and, shortly thereafter, she also withdrew from Wimbledon. To stand up for herself in this manner was an act of grace and courage. I don’t say that to burden Osaka with even more pressure or expectations she needs to live up to. I was just impressed with and moved by the way she prioritized her needs and did so without apology. I was envious because I struggle to imagine myself being able to do such a thing.

In cultural discourse, we talk a lot about boundaries, but it is, often, a theoretical discussion, a nice idea for the better versions of ourselves. Despite the lip service paid to boundaries, there is always intense discomfort when people establish boundaries and then dare to uphold them. We celebrate other people’s boundaries until those boundaries get in the way, keep us from something we want. When we encounter a boundary, we don’t like, all hell breaks loose, and then someone with boundaries is not brave or powerful; she is selfish or weak or arrogant or problematic. And people who are willing to transgress someone’s boundaries know this. It empowers them.

At the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, gymnast Simone Biles was going to be America’s bright shining star. Of course, she was already that, the greatest gymnast ever to practice the sport. Biles was also one of the countless young women who endured sexual abuse, for years, at the hands of Larry Nasser while the United States gymnastics establishment looked the other way and allowed a predator unfettered access to victims. During the US Classic in May 2021, she performed the Yurchenko Double Pike; she did it because, in her own words, she could. Biles was the first woman ever to perform the Yurchenko in competition—a roundoff back handspring onto the vault, and then powering herself into the air with enough time and space to flip her body twice in the pike position before landing and, hopefully, staying on her feet. She was the gymnast who performed a feat so incredible and challenging that the International Gymnastics Federation decided to score her physical feats “conservatively” to “discourage” other gymnasts from risking the dangerous moves she can do.

These gatekeepers literally punished Biles for being too excellent, for going too far beyond what was asked or expected of her. She vaulted through a glass ceiling and the gymnastics federation built a new one over her.

By the time the Olympics came around, it was clear Biles had achieved everything possible in her sport and then some. Despite the abuse she experienced, she remained the face of USA Gymnastics and gave them cover for their misdeeds with her incredible reputation and skill. Over the course of her career, Biles performed through trauma, injury, and fatigue. She carried the stress of competition and smiled her way through it. She owed the sport nothing, and still, she did what was asked, expected, and sometimes demanded of her. She showed up at an Olympics being held during a pandemic at which political protest was forbidden. And then, after a stumble off the vault, Biles withdrew first from the team competition and then from the Olympics entirely. It was another demonstration of grace and courage. There were critics, as you might expect. Her decision to prioritize herself suddenly became un-American despite everything she has done in the service of her country. Her boundaries were too inconvenient, and just like that, her critics decided to ignore every great thing Biles had ever done. In one instant, she became a problem.

We ask a lot of athletes. We valorize their physical and emotional suffering as a measure of excellence. Then we say these challenges are the price they pay to be competitive, to be the best. We say they knew what they were getting into when they decided to compete at an elite level. We also ask a lot of black women, expecting them to give endlessly of themselves, want nothing for themselves, and shoulder the expectations of others silently. We throw around a lot of labels for public figures, and especially black women in the public eye—warrior, champion, fierce, fearless, until we turn on them, and then the words we have for them are a lot less polite.