6th July 2022

Poetry

3 minutes read

The Legend of Lobo

translated by Diana Senechal

6th July 2022

3 minutes read

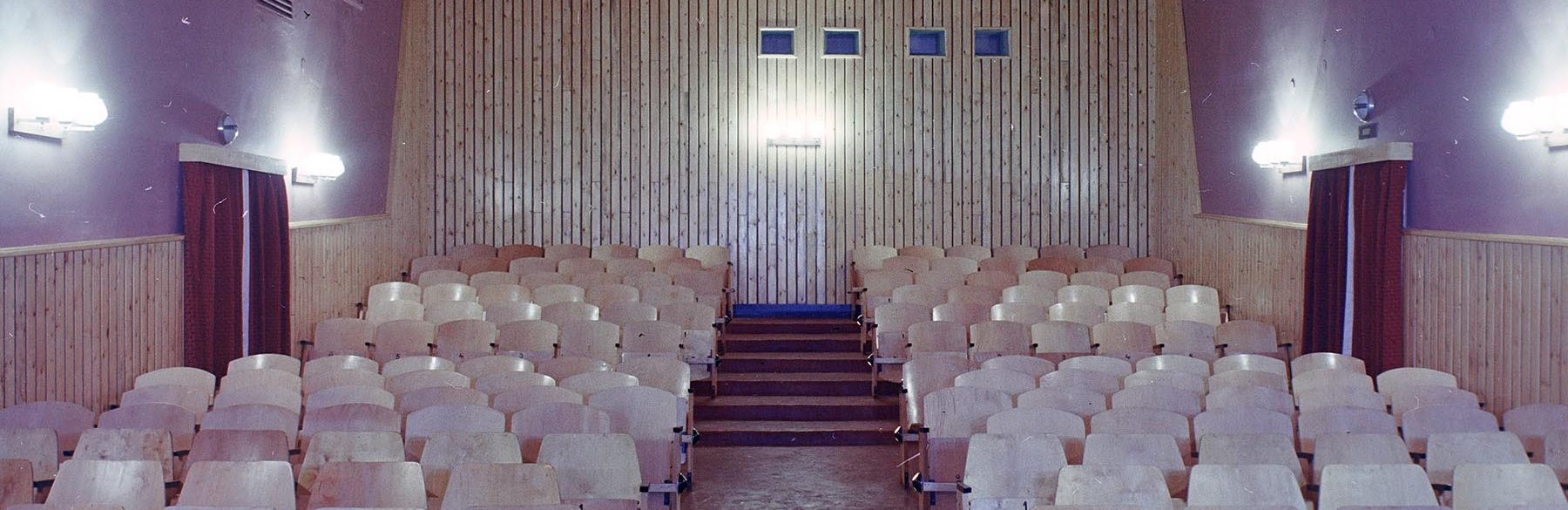

strip-jointed floor, oil-fired stove, two-hundred seat

auditorium to the world. we always buy tickets for

the twelfth row. the rearmost medium-priced row.

the entrance is five forints. for the first row, two. just once

will i sit up there, to see a soviet film. i have

to keep gazing upwards, my neck starts to hurt,

and the screen will be immense, and

the frames will flicker nervously.

there the poor people sit, the proles,

while the six-forint seats are for those who can afford them,

says my father. this places us in society: it classifies us,

separates the extremes. it is less painful to be in the middle.

the mustached, stocky old printer, who always comes

to the movies with his tall, bird-boned wife, regularly

buys tickets for the eleventh row, maybe because

the emergency exits are there, and thanks to the stove

on the right side of the hall, several rows are missing; so,

while watching the film, they can stretch out their legs.

the six-forint tickets sell less. my first motion picture

brings fear to mind. at that time, i do not know that

the wolf running toward the projector will not burst out

of the screen. i am terrified. my parents keep talking

about it long afterward. then i watch the other films:

from blossom time to autumn frost, timur and his squad,

amphibian man, osceola, i see hair there later too. my english-

learning classmates pronounce the title in at least

four different ways. the small town’s small high school.

a few jancsó films, the naked migration of women, amarcord:

that widescreen blue pullover, those astonishing breasts:

not desire, not disgust, pure amazement. when i am bigger

and i go with my friends to the movies, my favorite spots

will be in rows seventeen and twenty-two. kissing couples,

creaking seats, rattling paper bags. they shoot the godfather,

the oranges tumble and scatter. the buzzing aircraft

of the apocalypse. one time they do not admit minors,

but my classmate, two months my junior, gets in. later

the cinema goes out of business, closes down. i forget

the name of the old cloth-capped projectionist, the stout

cashier lady, whose mouth is eternally painted blood red,

and whose neck has a thick string of pearls looped

around it. when i write this, i look up the legend

of lobo on the internet. i watch it from start to finish.

that is how first love can be.

First published in Gyula Jenei’s poetry collection Always Different: Poems of Memory, translated by Diana Senechal (Dallas: Deep Vellum, 2022).