3rd May 2022

Non-Fiction

17 minutes read

Eight billion Shades – Capturing a World of Color

translated by Owen Good

3rd May 2022

17 minutes read

Kodak, one of the most familiar names on the market in the world of photography, launched research into ways in which to produce darker tones simply in response to interest from chocolate producers and furniture factories, that were increasingly impatient to have photographs that captured a diversity of shades.

At the beginning of the new millennium, I lived together with Sara Nordangard, a Swedish visual artist. As a child, Sara had lived in Tanzania. As a teenager, she had worked in Ecuador as part of an organization providing help for the Shuar indigenous people. She later moved to the United States. When we first met, she had been working in Columbia for more than a year. As Sara and I grew closer, we moved to Budapest to live together.

Sara told me many times that nowhere had she ever seen so many heads hung low, so many shades of dejection and despair, so many faces grown rigid with resignation as she saw in Hungary.

I, of course, am from this land known as Hungary, a distinctive country in the middle of Eastern Europe, and this shaped my attitude to the subject. As a country that fell under Soviet occupation after the Second World War, Hungary remained largely isolated for the latter half of the past century. When I was a child in the 1970s and 1980s when people from other continents or with other skin colors were rare. From time to time, one might happen across guest workers from Cuba who worked in the weaving mills lingering the areas around the buildings in which they were given lodgings or perhaps some of our communist comrades from Vietnam, whom we were proudly showing the many accomplishments we had made thanks to socialism. The vast majority of the country called itself white Caucasian or, more simply, Hungarian. The comparative homogeneity of the country was due in no small part to the fact that, in the wake of the First World War, the country was dramatically reduced in size, and only a very thin slice of the population of the territory which remained in Hungary regarded itself as belonging to a national minority. In my assessment, however, the fact that, as a consequence of Soviet occupation, the country was almost completely isolated from the rest of the world after the Second World War was every bit as important. People of different nations hardly mixed on the streets of Hungary at the time, and there was very little international tourism. It is perhaps also worth noting that, in contrast to many other nations, Hungary never had colonies overseas, which might have brought a broader spectrum of varying shades of skin to our country. For the first 15 years of my life, I learned of the world beyond the borders of my homeland from the books, articles, films, and other cultural products that were permitted by the censors and also from Austrian television. I have memories from my earlies years of political officers watching the Easter parade from the window of our childhood bedroom so that they could make a note of the Communist Party members who were indulging in the naughty sin of going out in the streets side-by-side with members of the Christian fold. I couldn’t quite say the precise extent to which my childhood experiences shaped the following rather pronounced feature of my personality, but from a very young age, I always felt that I had to take a stand in support of the vulnerable, the wronged. I have remained something of a hopeless romantic, an idealist, and I continue, unflappably, to search for justice and truth in everything and behind everything, and I have never feared confrontation, even a potentially risky confrontation, if necessary to defend my truths, whether real or perceived. The romantic flights of fancy on which I embarked as a youth often took me to the oppressed American Indians in Yugoslav films, who were presented in the films of the Tito era in stories every bit as lovable as they were misleading. Sometimes, I imagined myself in a village in Africa, entirely cut off from the rest of the world, but fleeing oppressive reality. A lot of time has passed since then. The reveries of my childhood, the lure of the arts, and my parents’ unquenchable thirst for culture created a path that led, almost straight as an arrow, to the visual arts. Today, I direct films, work as the head of art projects, and have been photographing, for a good 20 years now, tribal cultures and the worlds of smaller ethnic groups and peoples. Most often, peoples whose visual culture is on the verge or even the precipice of disappearing altogether, for these people leave the elements of their visual cultures by the wayside first, then their religions, and then their languages begin to vanish underneath the immense economic, social, and political pressures of the outside world. And thus, the yearnings of the child eager to explore the world and the visions of the romantic met with the determined man of the arts who in the meantime had grown into an adult. (At the moment, I am working in the tribal territories of Ethiopia, which is being plunged into civil war, and India. Earlier, I worked in almost every region of South America and Africa and also in Asia, more specifically India and southeast Asia.) In my work, I have taken photographs of people of a vast array of skin colors. The differences in their appearances interested me for only two specific reasons: their relevance from the perspective of cultural anthropology and the technical questions concerning photography. I was asked to share my thoughts in his essay because of the latter interest, but I still feel it important to address the question in its complexity, which is why I have touched on my homeland and a few of the ups and downs of my youth. Thus, I should write on the aspects of making photographs of people of color.

At first, I didn’t understand exactly what this meant, since after all, we are all people of some color.

I wondered, furthermore, how I could begin to approach this tricky question without leaving myself vulnerable to attacks on innumerable fronts. There are shades of skin that are lighter and others that are darker, and the task of capturing these shades demands solutions from the perspective of photographic technology. The rest, however, is hardly an issue. According to one of the most widespread theories of color, white is simply all of the colors of the spectrum at once and black is the absence of color. I hope that the following question no longer comes up nowadays, but I still must pause for a moment to make a note of it: there are on this planet no white-skinned people and no black-skinned people. Rather, there are human beings with skin of almost eight billion different shades, people whose skin is as unique as their fingerprints. With our skin tones, moles, warts, blemishes, and scars acquired over the years, we are all unique. While writing this article, on a Sunday night I was an engaged fan of a jazz ballet competition, and I watched the arms and legs of the dancers performing in groups, the shades of their skin during their performances. They were almost all Hungarian, but I could not find two people with the same skin color. I have been working with light and shade in millions of colors for nearly thirty years now. When I was a child, one of my father’s friends asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. I must have been about five years old at the time. Miklós, my father’s friend, was coming home from a hunting outing with my dad, and when I saw their rifles, I immediately said I wanted to be a hunter, “because you know,” they looked so manly with their weapons in hand. Then, a moment later, I added, “and light and shimmer, I want to be light and shimmer too!” So I became a hunter of light. For me, the color of the subject of the photograph, the tone of his or her skin, is a matter of artistic consideration and should be nothing more. But it’s not quite that simple, because my work as a photographer is motivated primarily by my interest in cultural anthropology. Beyond the simple technical questions, I am also preoccupied with the cultural and anthropological aspects of skin color. The skin tone that is specific to a given ethnic group is visible in the images, and it is not racist to talk about this. In Africa, I was never surprised or indignant to hear people identify me by my skin color. When I was working in the Congo, I was repeatedly called mundelé, or white man. I lived in Uganda from 2013–2014, where locals usually called me white, and when I was working in East Africa, I constantly heard the term mzungu, which was used to refer to me based on my skin color. Never, however, did I feel that it was racist for a vendor at the Kampala market to call me a mzungu if he or she did not know my name and instead simply referred to me as a white man when asking, with a broad grin, which kind of dried fish I wanted. Context determines what I think about what is said, and I need not react too sensitively to a problem that does not exist in the given situation. Back home in Budapest, however, I had a very different experience with this touchy issue. When fate saw fit to bring me back from Uganda in 2014, my Lugbara wife came with me. The Lugbara are a group of about seven million people who live in the northern part of Uganda. The tribe migrated south to the region from southern Sudan a few hundred years ago.

I found myself compelled to rethink Hungarian hospitality and the unusual Hungarian existence in Central Europe.

On countless occasions, my Ugandan wife and I heard hostile remarks being made around us and comments that gave voice to racial prejudice. On the street, in restaurants, and bars, more than once we were given unsolicited advice as to where my wife, whose skin is of a strikingly dark tone even in Central Africa, should go, but essentially, that she should not remain here. At times, we were even physically accosted. It’s true that Mercy, my wife, was not willing to suffer insult or injustice, perceived or real, in silence. Alas, the changes which are underway at the moment the world over, which include political radicalization, nations turning inward, and modern-day population movements and displacement (tied in some cases to climate change) are hardly helping Hungary be more open to people from other continents. My homeland’s conduct very precisely reflects the political past and the uncertainty of the present. The desire to remain isolated from foreigners, the hostile approach to the refugee question, and intolerance towards the gay community are all very palpable.

By the twenty-first century, photography had embarked on a dramatic liberalization. The photograph has become the most widespread folk art of our time. The dizzying speed with which smartphones have become an ever-present part of our everyday lives has given billions of people access to cameras of which they make bold use. With the rise of audio-visual devices, visual languages are becoming increasingly important, and the Guttenberg galaxy is undergoing a transformation that makes earlier centuries seem like still waters compared to the changes of the past few decades. Modern smartphones are slowly making their way into the most hidden corners of the world. Anyone can take a picture almost anywhere, and by the end of 2021, some 1.4 trillion pictures will have been taken if the trend continues. The planet is shrinking, and one can get to almost any settlement in the world within 24 hours. Cultures create images of other cultures with no strings attached. Skin color is no longer a question, and it has not been a question for some time now. But this wasn’t always the case, neither in a cultural nor in a technical sense. In times past, it was often the explorers who created images and made records of other cultures. The journeys and ventures of the great pioneers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries produced a wealth of visual documentation, a significant share of which consisted of photographs. Initially, the native inhabitants of “newly discovered” lands were treated condescendingly, as a kind of inferior species. The unmerited scorn with which natives were looked upon was whittled away by people with pioneering minds, such as Emil Torday of Hungary. In 1903, Torday traveled as a civil servant to the Congo, which was a Belgian colony at the time.

He had dreamed of Africa as a child, as had I.

While working in the Congo, he learned six local languages and, in a departure from prevailing practice at the time, he mingled with the peoples of the local tribes, whom he regarded as his equals, and collected data. He did not do as most of his European contemporaries did and summon the locals to question them. Rather, settling among them on their lands, he spoke to them in their language. Today, this might not seem like such a strikingly virtuous deed, but one should keep in mind the attitudes of Victorian England towards the indigenous peoples of the colonies. From 1906 to 1909, Torday led expeditions on behalf of the British Museum. He took more than 4,000 photographs, and the material he collected makes up a significant part of the museum’s collection of artifacts from west Africa. The objects he exhibited at the British Museum, including plant weavings with geometric designs from the Kuba Kingdom, ornate textiles, and masks, had a huge influence on modern art and the age of the isms. (Unfortunately, the Torday sound recordings on wax cylinders were destroyed when a fire broke out in the museum’s storage space.) The continent of Africa has changed a great deal since then. Today, there are photographers all over Africa whose names are worth knowing, photographers who have played important roles in the history of photography, and whose contemporary work is outstanding, year in, year out. I would mention only a few important names. Seydou Keïta made exciting portrait photographs in the 1940s and 1950s. Malick Sidibé and Ricardo Rangel were important photographers in the 1960s and 1970s. The socio-photographs of Santu Mofokeng also deserve mention, as do the beautifully colorful portraits by Rotimi Fani-Kayode from the 1980s. And among the contemporaries, I could hardly leave out Lakin Ogunbanwo, whose work lies somewhere on the border between fashion photography and art, or Brian Otieno, with his snapshots of everyday Africa. Aïda Muluneh captured my gaze and won my heart with her amazingly delicate compositions, and the work of Mário Macilau reminds me of Sebastião Salgado every time I see it.

If one turns to the technical questions, there is a hefty body of literature on taking photographs of darker skin colors, and it is a very sensitive subject. Countless publications have been written on how to photograph people with darker skin tones. Many people not adequately knowledgeable on the subject take the issue as a racial issue, pro and con, often bending the facts to suit their political goals and perceptions. Many people, for example, believe that photography in American culture looks back on a long tradition of misrepresenting dark skin in a deliberately misleading and distorted way. I cannot know whether this is the case or not, which is why, in part, I wrote at such length about the evolution of my Central European perspective.

The facts, however, cannot be ignored.

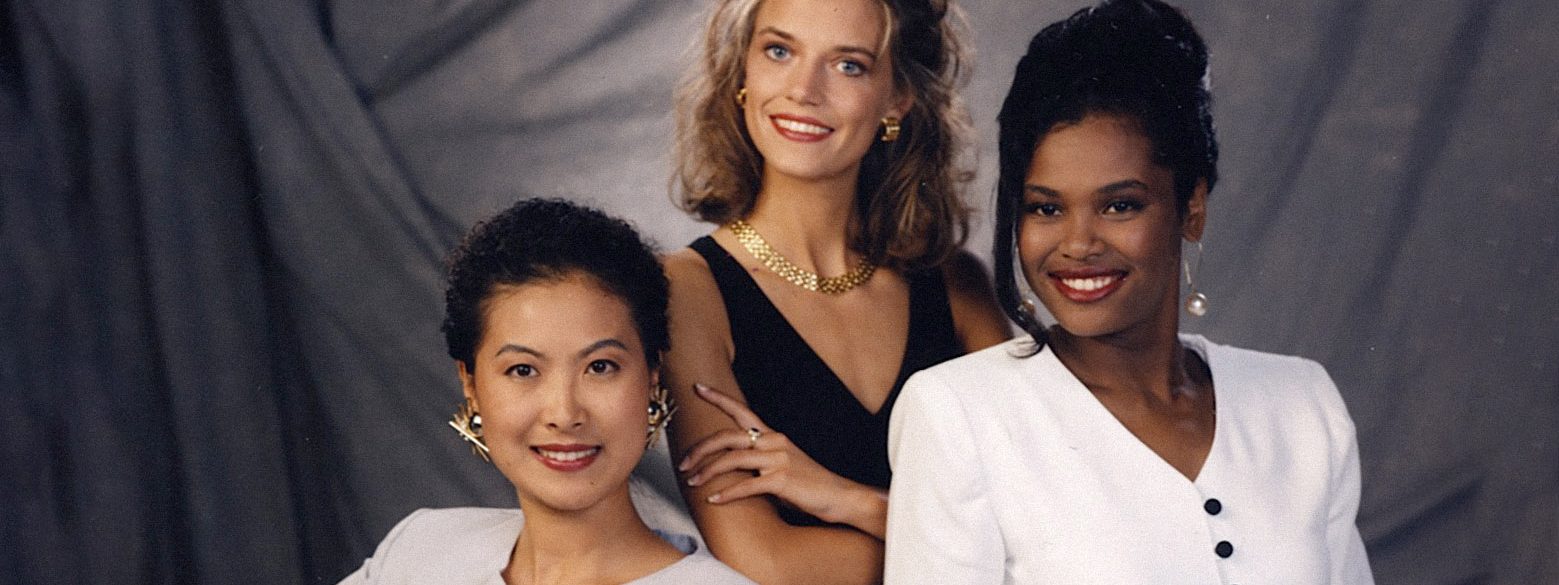

From a historical perspective, we know that the arguably never-ending process of regarding all human beings as equals began long, long ago. But let’s stick to the technical issues. Kodak, one of the most widely-known players in the world of photography, only started searching for solutions to the problems of the photographic reproduction of darker tones because chocolate companies and furniture companies which produced darker items were becoming increasingly impatient in their demands for photographs that captured darker shades. Some of the darker tones of the furniture and chocolate that were coming into fashion were hard to distinguish using the films available at the time. This caused modeling and color problems, and the result was flat images with no detail when the tones concerned were involved. This was all taking place in the 1960s and the early 1970s, towards the end of which television and show business were increasingly liberalized and the ever-growing number of skin tones appearing on screen in an array of shades began to demand change. At the time, the famous Kodak Shirley card depicted only a white woman, and this was used to enable lab technicians and emulsion developers to display the correct skin tone on the images. A later Shirley card showed three women. In addition to the white woman in the middle, on the right, there was a woman with brown skin and on the left, there was an Asian woman. This card was called the multiracial Shirley card. Celluloid film was still in use at the time, on which emulsion layers bore the colors. The chemicals and liquids used in the process of development captured the appropriate tones. (I am thinking of color film, of course.) The photographs of dark-skinned people made using the materials and processes of the time were not impressive.

Details were lost, and everything blurred into black.

The same materials and procedures produced pleasing results for white skin tones. Thus, types of film were being developed at the time for a market and for a set of expectations that were centered around depictions of people with lighter shades of skin. This does not necessarily imply an arrogantly or intentionally racist mindset, but it certainly demonstrates that little consideration was given to the question of photographs made of people with darker shades of skin, and this faithfully reflects the political and social climate of the time. From the perspectives of economics and human rights, this is where the United States was at the time. With modern cameras, digital cameras, color scaling is no longer hampered by these kinds of problems, but as a practicing photographer, I know all too well how important it is to pay attention to how large and how many stops there are and there can be in a given photographic composition. In the case of a light face illuminated in a very dark room, the poorly lit background, the room, may well be completely lost in the blackness of the shadows. Conversely, if I shine light on someone with dark brown skin sitting in the shadows, the sunny blue sky can easily become a white blur devoid of any detail. There are innumerable websites, articles, and YouTube videos on the internet offering advice on how to photograph people with darker skin tones, but nowadays, this is merely a problem concerning photographic technology and technique. In theory, the big camera manufacturers are careful to ensure that their cameras can faithfully capture all skin tones. They do this in part for economic reasons, since cameras are now bought all over the world, and the subjects they are intended to provide depictions of are immensely diverse. Manufacturers must be cautious not to allow even the slightest suspicion of discrimination to fall on them, which, however, is not to say that there have not been any problems with this in recent years. Accusations have been leveled at Microsoft’s Kinect camera and HP’s webcam, which had a motion-tracking algorithm but failed to recognize dark-skinned customers.

The moral of the story? There isn’t any, and I never expect there to be.

We are all here, nearly eight billion of us, and we all have different ideas about the world, much as we all have different skin colors. The world is rich with shades of color, and it will be beautiful as long as we can keep it that way. Sooner or later, societies based on uniform expectations become dictatorships, both politically and culturally.