16th August 2022

Fiction

8 minutes read

Inscrutable Are Ways of Tengri

translated by Thomas Cooper

16th August 2022

8 minutes read

“And what the fuck do you wanna buy a yurt for if you don’t even know what a yurt is?” Szabolcs shouted into the phone.

Early afternoon. Scents of rain.

Not raining yet. But soon.

Clouds loafing across the sky. Rusty branches rattling in the lowland breeze. Szabolcs with his cellphone in one hand, pressed to his ear, and a bucket in the other. Taking leaves from the walnut tree to the goats. Raking them up for them in the morning.

“Goats love walnut leaves.

Goats love everything, from tractor tires to walnut leaves.

Goats eat anything they can chew up. And goats can chew up pretty much anything. Goats were sacred animals to the ancient Greeks. And you gotta treat them like sacred animals.”

“What’s this crap about goats and ancient Greeks?” said the voice on the other line.

“Wasn’t talking to you,” Szabolcs replied.

“Then who were you talking to?”

“Myself.”

Szabolcs had been talking to himself a lot ever since he had been living alone on the farm. Mumbling. Constantly. To himself.

He kept plodding along, carrying the bucket full of leaves and yammering on the phone, and suddenly he realized, in the middle of his yammering, that oh right, he doesn’t have any goats anymore. Emese took them when she went. All seven. Two billies, Bendegúz and Termecsü, named after a fierce Hun king and a Hungarian leader of yore. Two mama goats, Bubus, a demon from ancient Hungarian myths, and Vadamerca, wife of an ancient Hun ruler. Two kids, Réka and Mikolt, wives of the great Attila, scourge of God, and one fawn, little Koppányka, named after the first Hungarian king. He had been the their favorite.

She had taken the horses too, both of them, Mókár, named after another demon from the lore of yesteryear, and Táltos, the word for the shaman among the ancient Huns.

And the black cat, Ürdüngö. Or devilish one.

Left the dog. A Hungarian vizsla, as it so happens. Attila, of course. As in the Hun.

“Excuse me, sir, I’ll call you right back,” Szabolcs said, and he hung up. He threw the bucket to the ground and stomped on it, swearing all the while, until he had smashed it to pieces. He then kicked about twenty pounds of hot peppers with his rubber boots. Spicy peppers flying in all directions.

“Fuck the whole fucking fuck for fuck’s sake…” For a good quarter hour.

Ever since Emese had left, he had had frequent fits of rage. He shattered her fancy full-length Viennese art nouveau mirror, for instance, which for some reason she hadn’t bothered to take with her when she had left.

But she had taken everything else. Except the mirror.

Though it had been passed down from generation to generation in her family. It had belonged to her great-grandmother, who had lived a life of glitter and glitz as the wife of a jeweler in Bratislava. Why hadn’t Emese taken it with her? Szabolcs still didn’t get it. When she had moved out for good, a truck had pulled up at the gate and four young men with big, strong hands had tossed all Emese’s stuff into the back. Her wardrobe, her wide-screen TV, the pets. Everything. Except the mirror.

Once he had kicked the peppers hither and thither, Szabolcs knocked back a gulp of stiff quince pálinka. Homemade quince pálinka. Hadn’t been any peaches for some two years now, so he’d taken to drinking quince. Not too far away was a distillery, where he took the mash for a test run. He didn’t want to mix his stuff with other people’s rot. Better to drink your own brew. He tilted back the bottle, swished the pálinka around in his mouth a little, and gulped it down.

“Pretty good,” he said in a whisper. “At least that’s still good.”

Since Emese had left, Szabolcs’s pálinka consumption had increased considerably.

Over the course of six months, he had drunk as much pálinka as he usually would have had in two or three years.

He could feel the pressure in his head.

He stuck his head into the battered iron tub full of rainwater next to one of the hoop houses. He pulled his head out and brushed back his hair. He tried to calm down a little. He realized, looking at the tub, that he hadn’t bathed in months. Nor had he shaved. When Emese had been around, he had taken a bath every week. But no one to clean himself up for now. The dog? Or the chickens and the geese?

Another gulp of pálinka. Feeling a little more relaxed. He called back the man who had taken an interest in the yurt.

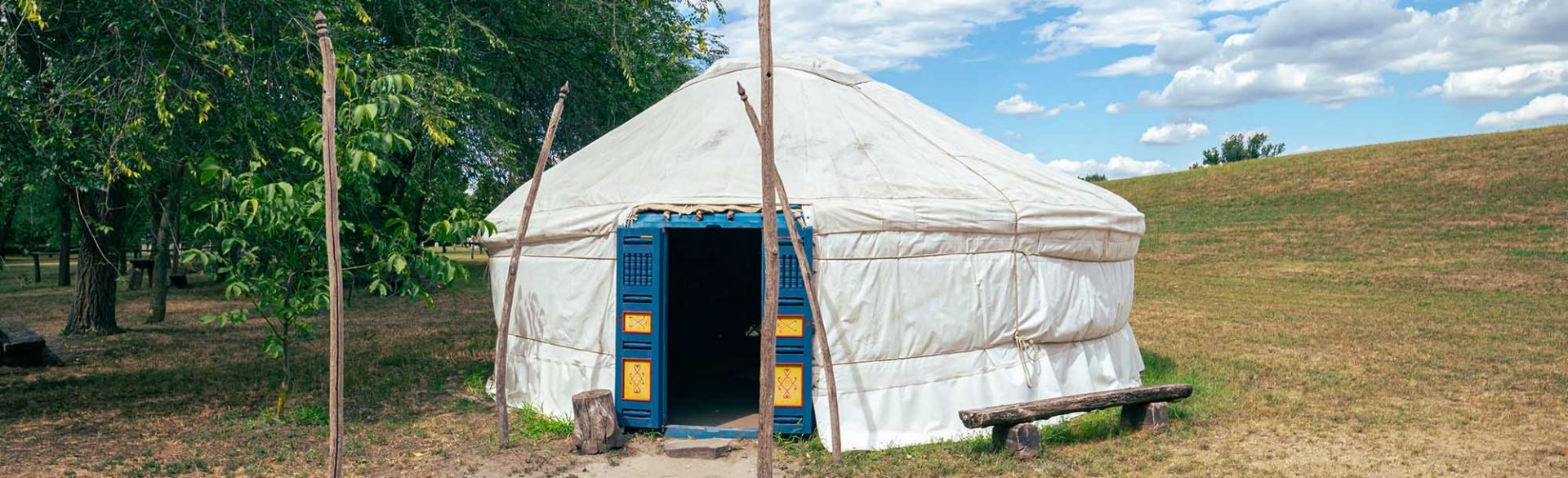

“So, if you must know, a yurt is pretty much a tent. A circular tent. A very practical thing. The Huns lived in yurts about a millennium and a half years ago, when they lived here on the banks of the Tisza River. The felt is waterproof, and it holds the heat in pretty good. Made from the wool of merino sheep. The Huns kept their suckling animals on either side of the entrance. They had an oven or a stove in the middle that they used to cook their food in the winter. They used big iron cauldrons. The smoke escapes through a hole in the top of the yurt. Male guests would sit in front of the fire, to the right, female guests to the left. The head of the family sat in the place of honor behind the fire, on the right, and the women and children sat on the left. The family’s possessions and household gods were kept just behind the spot reserved for the head of the household, and the kitchen utensils were at the back on the woman’s side. The bed was also on the woman’s side. When the head of the family wanted to lie with his wife, he would simply go to the woman’s side, gently nudge his snoring children to one side, and give his lady a good screw.”

Bewildered silence on the other end of the line.

It had started to rain.

“I see,” Szabolcs says. “Quite right. You didn’t ask about the Huns, you asked about the yurt. I was just trying to put it in its historical context… So, our yurt, or my yurt, is a precise replica of the yurts used by the Huns. It has an oven, a bed, a chest, a shrine, everything. And electricity and Wi-Fi. My girlfriend and I lived in it. For eleven years.”

Attila, the Hungarian vizsla, snuggled up to Szabolcs’s feet and let out two yaps. Szabolcs understood. Attila was suggesting that they go into the yurt because it was raining harder and harder. They went into the yurt.

“What happened? What do you mean what happened? That ain’t none of your business! That’s a private matter. Let’s just say that our relationship ended.

Did we have kids? No, we didn’t have kids.

But that’s none of your business, for fuck’s sake! Why the fuck are you interrogating me? Tell you what, if you want to take a look, come take a look. At the yurt and the land. And if you want them, we’ll agree on a price. I’ll give you the address, and I’ll let you know what I’m thinking of when it comes to price.”

“Look young man, you’ve got an embarrassing little hankering for love. Love’s nothing but suffering, enough to lay a man low! You think love is happiness? Think again. How the fuck could something so dark and disturbing be happiness? Truth be told, it’s world literature that’s to blame. World literature convinced everyone of this bullshit. And there are so many other beautiful things out there to hanker after! Trust me, I’ve been around quite some time now. There’s death, for instance. Ah, death, alluring, enduring death”

Szabolcs hung up. He knew he’d been shooting his mouth off again, and for what? Another nutjob. And this guy’s not going to drop by either. Szabolcs had been running an ad for the yurt for months, and not a single person had taken any serious interest.

Nobody wants to live in a yurt.

People want to live in houses made of brick and stone. Or at least drywall. Life isn’t a camping trip, after all. Though actually, Szabolcs thought, life is a hell of a lot like a camping trip. You pitch your tent when you find a pretty spot, the weather is good, and the sea’s not too far away. Then, when you get bored or the weather turns sour, you pull up the stakes, pack up the poles, roll up the tent, and move on.