15th June 2022

Interview

14 minutes read

I translated at least 50 Native American poets

15th June 2022

14 minutes read

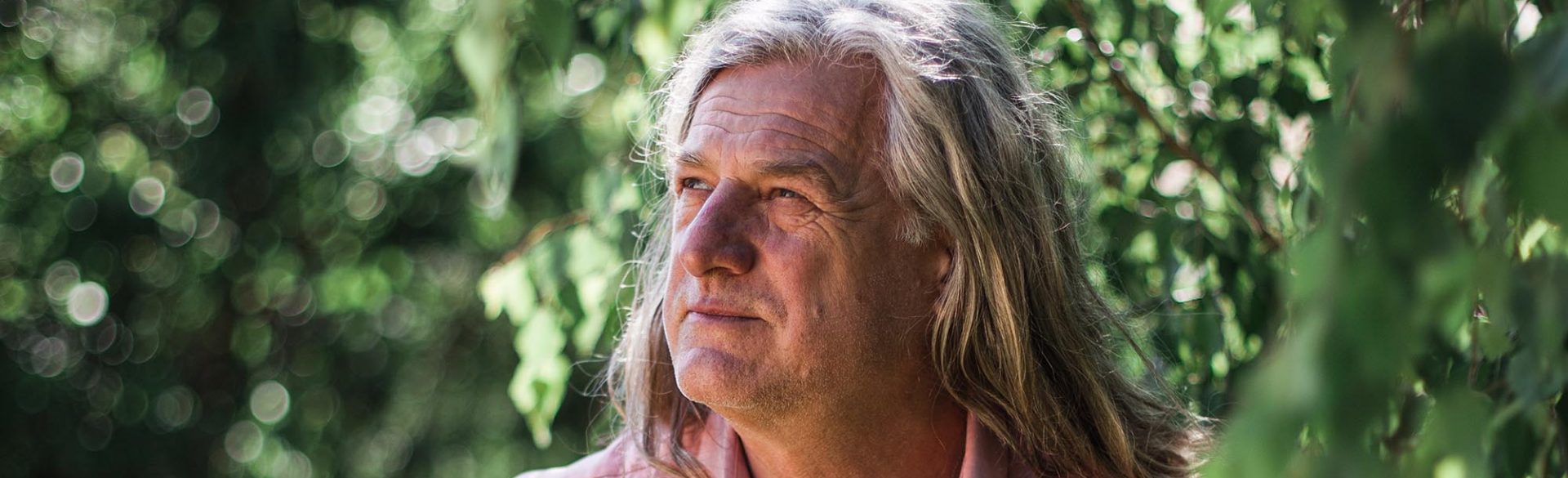

Hungarian poet and translator Gábor Gyukics talks about leaving Hungary in the 80s as a political refugee, his time living, writing and publishing in the US, and his years of translating Native American poetry.

Sándor Jászberényi: You left Hungary in 1986. Where did you go?

Gábor Gyukics.: Yes, I left Hungary in 1986, I purchased a fake passport from an acquaintance of mine who I usually met at jazz concerts but had just gotten out of prison, so I knocked on his door and he said: “Well, business never stops”, so I said, “Good because I need a passport”.

He took my 500 Forints (1.75 USD) and I flew to Amsterdam. They interrogated me at the airport for a few hours and then let me go because I had visas to Germany and France, and said I was hitchhiking back to Hungary after I visited Holland. A week later I went to the foreign police and applied for status as a political refugee, which I never received in Holland. But some good old Kisfa gang members took me under their wing and I lived with them. During that month, I figured out they were all junkies, shooting up heroin, cocaine, and all kinds of weird heavy stuff. I was smoking weed and hash but that was it. They introduced me to other guys who were dealing with literature and theatre, and who prompted me to start writing poetry. I stayed in Amsterdam for two years and I have to tell you, I had a great time.

S.J.: Why did you have to leave Amsterdam?

G.Gy.: I had to leave Amsterdam because during my last year in Amsterdam I was an illegal resident. After applying to Australia and Canada who refused me, I applied to the US and had to go to Brussels to talk to the US ambassador and he knew everything about me. I was completely surprised. He knew I had long hair, knew I happened to be in theatres and hung out with the Kisfa gang, and I got permission to move to the States. So, in 1988, on October 31 – Halloween night – I arrived at JFK Airport in New York. And then flew to Saint Louis, Missouri where I stayed for two years. Two good years actually.

I met a lot of good people there, including my translator, the late Michael Castro, who helped me with my English, my translation project, and my poetry. He had a radio show and aired my poems which I read in English, so by that time I was writing poetry in English and translating Hungarian poetry.

I translated Traveler and Moonlight by Antal Szerb into English.

I don’t have the manuscript, but that improved my English a lot.

I lived in Saint Louis, and I played in theatres. I think my first role was the waiter in Betrayal by Harold Pinter. I then moved to Saint Francisco, where I lived for four years and finished Traveller and Moonlight. I had so many people editing that book, helping me with the language and that’s where I met several beat poets. Caffe Trieste is where I met Lawrence Ferlinghetti and other great American poets. Jack Hirschman – that’s where the whole jazz poetry thing started among the white poets when Jack Kerouac and David Amram did their first jazz poetry gigs. Of course, I met so many others whose names I don’t remember, but in San Francisco, I was mainly acting. I made several films, they weren’t hits, I think one made it to video and is available somewhere, but I don’t remember.

After four years I moved to Brooklyn, New York, and met Ira Cohen who introduced me to Ginsberg. I hung out with the Ginsberg entourage and with Ginsberg as well, went to several of their readings and to the Nuyorican Poets Cafe a lot, where my first slam experience happened. I participated in the slam events there for years, but never won – I wasn’t that good. The Black and Hispanic poets just blew my mind, what they were doing was, well, nothing in Hungary could do that ever.

Then I started publishing in magazines. I lived in New York for eight years, I had several jobs. During my 40 years in the States, I had several different positions. My last two were in parallel: librarian at both the New Jersey Historical Museum and at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Many things happened, I made many good friends,

met Gregory Corso, saw William Burroughs reading in Saint Louis,

I have a good story about that. Nothing else comes to mind. I came back to Hungary and then returned to the US for six months. That was the time when I met my first Native American poet.

S.J.: Tell me the story: how was the reading with William Burroughs?

G.Gy.: OK! Washington University invited Burroughs for a reading because he was born in St. Louis, on Pershing Street – I lived just two houses down from the house he grew up in. The auditorium was packed with students and professors and me. He was talking and at one point he said, “I have to take a leak, gotta go to the loo!” so he left, and never came back! The organizers started searching for William Burroughs and found him in a different auditorium smoking a huge joint, and he said “I’m not fucking going back there anymore, I’m done!”

S.J.: How did you end up being the number one translator of Native American poetry?

G.Gy.: When I went back to St. Louis to visit my friend, Michael Castro, and some other great poets, I met an Osage Indian, a Native American, named Carter Revard, who is probably eighty-something now. He was the professor of English literature, I think he graduated from Oxford, summa cum laude or whatever you call it, and from Yale – two of the world’s great universities. He had never met a Hungarian and I had never met a Native American. We started talking and I invited him to give a lecture, a poetry reading at Petőfi Literary Museum in Budapest. I think it was 2005 and there was a great crowd. He came back a few years later and did another good reading, his poetry wasn’t the first that I translated but the last time he left Hungary he told me “Gábor, I’m not the only Native American poet” so I said, ” don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to be sarcastic, please send the smoke signals to the other Native Americans that there’s a crazy Hungarian who wants to read their poetry and translate them into Hungarian. If they don’t mind being translated into a language which is only spoken by 15 million people.” So I got a lot of poetry, at least 50-60 people and then there was no stopping it, I had to go on and I’m still translating for Native Americans. I visited the Flandreau Reservation as well, where Jim Northrup lived. I published his book, and I published a Native American poetry anthology five years ago as well. So two Native American books. And I translated one of my favorites, Lance Henson – he’s an exile because he’s a revolutionary, and they don’t like it when he goes back to the States because there is always turmoil when he goes back. I think he used to work for the United Nations dealing with indigenous issues, so he went to Papua New Guinea and other places around there. He visited the Natives and tried to voice their struG.Gy.les to UN authorities. He is a great poet and writes very short poetry like my mine. He is kind of a minimalist but it’s very strong stuff, and it turns out that he was a Dog Soldier, who are known to be fearless Native American warriors.

S.J.: How did you get in touch with the Dog Soldiers?

G.Gy.: The way I got in touch with the Dog Soldiers was to just call Lance and see what he says. I mean he tells me that this is a very old society of the Cheyenne tribe. When the first white people arrived, the Cheyenne gathered together and decided they have to fight these people, so they assembled many people and created a warrior society called the Dog Soldiers, and Lance, as well as his son, are members of this society. And one of the rules – and I think still is, but it might not apply for new members – was that

you had to kill someone in combat to become a Dog Soldier

– you can’t just rob a house and kill the lady there and the nurse, you have to kill someone in combat to be accepted.

S.J.: As a translator of Native American Poetry, how do you see the situation of the Native Americans in these difficult times…

G.Gy.: Well, in general, I see that the Native American situation in America is very tough and possibly harder than the black people’s situation there. Minorities are not treated well by either the Republicans or the Democrats or anyone else for that matter. Racism is on the rise, right-wing groups are on the rise. Armed right-wingers! And they hate people of color. Period. Native Americans are prime targets of these right-wing groups. More Native American women disappear every year than from any other minority group. They are raped and killed by white policemen, white sheriffs, white hunters, and farmers, who don’t get punished. That’s a scandal, and nobody does anything about it. The Native Americans raise their voices sometimes, but they get no answers or responses. So they have to deal with this. They can’t figure it out, I don’t know how they want to protect their children but it’s very hard for them because so many tribes are living in poverty. Some groups got lucky because of the casinos and in other ways, but many, I think there is an Apache section, you go into their reservation, and it’s like the ghetto. It’s terrible – no running water.

S.J.: How many Native American poets did you translate?

G.Gy.: Native American poetry and art are very strong, and I translated at least 50 but probably more, Native American poets. I do it daily so I always pick up new people and because several young poets are emerging now, so probably 50 to 60.

S.J.: When you are visiting the States and visiting Native American poets, how do they treat you? How do they welcome you?

G.Gy.:

The Native Americans treat white people differently.

If you are an American white person, they don’t like you. If you are European, there’s a chance they will like you a bit more. But they give you a test. At first, you don’t even realize it’s a test. They start pushing you. They say nasty things. And if you get offended, they don’t care for you anymore. If you take it and answer with humor they laugh and say “OK! He is a nice guy!”

S.J.: Tell me your acceptance. Did it happen to you?

G.Gy.: When I arrived in Duluth and Jim Northrup and his wife picked me up. They were really nasty to me the first ten minutes, I was sitting in the back of the car, saying to myself “fuck man”. And then I started saying nasty things back, and they started laughing. I don’t remember the exact words. The next morning, when I walked into the dining area, Jim’s wife Pat, a Dakota tribal woman said, “I didn’t make no breakfast for you but there’s coffee”. Jim was sitting there too and I said, “OK, what am I going to do, that’s some nice hospitality.” So I poured some coffee and went to the fridge, took out the buffalo meat, and made a good breakfast for myself. I saw from the corner of my eyes that they were smiling, like “OK, he feels at home!” So I became a member of the family. They were testing me. Twice in twenty-four hours. Which I think is what they do with white people. And I know that the Native Americans really welcome Europeans but only those who really care about them. So if you want to cheat them or hurt them, they realize that fast enough and kick you out.

S.J.: Do you get any discount in the casinos because you are the translator of Native American poetry?

G.Gy.: I did get some discounts but I didn’t play. It was the Black Bear Casino in the Fond du Lac reservation; there’s a huge casino and I saw only white people playing – no Native Americans. The Native Americans were working there in different positions, just like in the movies. Coffee, cigarettes, you can smoke in the Native American casinos. The one-armed bandits, play two or three machines at the same time. It was there that Jim told me he owns a Corvette. Native Americans, only the ladies, play bingo and Jim’s wife won a Corvette playing bingo. She has never driven it, but Jim did, and once he took me for a ride to the casino. When we got out of the car, white people were going in with their sombreros, saying, “wow look at that Indian, he’s walking around like he owns the casino.” Jim turned and said “you bet,” because he does! The whole tribe owns the casino, and the money helps the reservation. They have their own hospitals and schools, a nursing home for the elderly, their own Native American police force, and grocery stores. They don’t have bars though – you have to go to the city for those. If houses get a little bit run down, the tribe votes for fifty thousand dollars of casino money to rebuild the house. So, the casino helps some Natives big time. But I’m not a gambler.

S.J.: Do the Native American poets want to be translated to different languages or reach out to the world? …

G.Gy.: Well, not really. If you go to them, some might say “No, I don’t want to get translated. I’m fine with my English”. They don’t work for it, they don’t say, “I want to be in Spanish”. Most said yes to me, but two young men told me not to translate their poems. But I don’t think that there are many Native American poems in other languages… maybe Norwegian, or other Scandinavian languages and Hungarian, that’s all that I know of. Except for Spanish, but I don’t speak Spanish, so I don’t know that for a fact.

S.J.: What is this obsession of Europe with Native Americans? Why are we so interested in Native Americans?

G.Gy.: Well, I don’t really know.

Some people say that the Hungarians one thousand years ago looked like and lived like the Native Americans.

Which, I don’t know – I wasn’t alive one thousand years ago. I think when Ervin Baktay and some other people visited Native Americans, they were accepted and taken in and these people came back and said nice things about them. Also, these James Fenimore Cooper books and Mark Twain books came out and so people – and I don’t want to offend anyone – but probably inside they think we like this “wild lifestyle”, and we want to be “wild” like these Indians. If you ask a Hungarian Indian, he would deny this but deep inside that’s what it is, I think. I never wanted to be an Indian.

S.J.: Why do you find Native American poetry worth translating?

G.Gy.:Because they are much smarter than we are at certain things. They are luckier because when a Native American becomes an intellectual, goes to high school then university, they read everything outside of their territories: Japanese literature, Chinese, Arabic, European, everything, and incorporate that with their own traditions, their own life, their own thinking, then put that into poetry or art. That’s much more interesting than anything else I’ve ever seen. That’s why I like it more. Hey, I like Sufi poetry too but I think Native American poetry is much deeper.