About the Issue

Youth Captured in Pixels

“Beauty is youth, youth beauty,” as John Keats almost wrote. At least in Central Europe, there is rarely a wedding, baptism, high school graduation, or even simple family gathering where words resembling these are not heard, usually from the mouths of grandmothers and great-grandmothers who are gently wiping the tears of joy and adoration from their eyes. These same grandmothers try to embolden their teenager grandchildren, who are wandering through mazes of self-doubt and beset with anxieties over their looks, with a hasty dismissal: “nonsense! Young people are all beautiful!”

Even the elderly of olden times, who had little chance to see much of the world and often even struggled to read, even they knew this simple truth, a truth perhaps coded into our DNA yet these days pushed in our faces by the advertisements in which we are inundated: youth is beauty. Stay young and you will stay beautiful. The two words have become almost inseparable.

We live in an era in which human beauty has an unprecedented value. Simply being “seen” on the innumerable social media platforms has become the confirmation of our existence, even if we don’t necessarily have any accomplishments to boast of. A few hundred years ago, beauty and its many accessories were the privilege of those who strutted through the vaulted chambers of royal courts. Today, they are accessible to almost everyone, and beauty has become as much an expectation as it is an aspiration. We no longer need court painters or family portrait painters. We ourselves have become the artists, and we produce, almost ad infinitum, portraits of ourselves in the most trivial situations, portraits clicked without purpose or meaning, and then we flood our social media pages with them. In the selfie culture of today, it has become perfectly natural to use virtual erasers to remove from our self-portraits anything that we find even mildly objectionable. And lo, Instagram has become a never-ending stream of images of ideal beauty crafted by the practitioners of one of the most popular callings of our time: digital content creators. Beauty and youth have become commodities for mass consumption, like bread and milk.

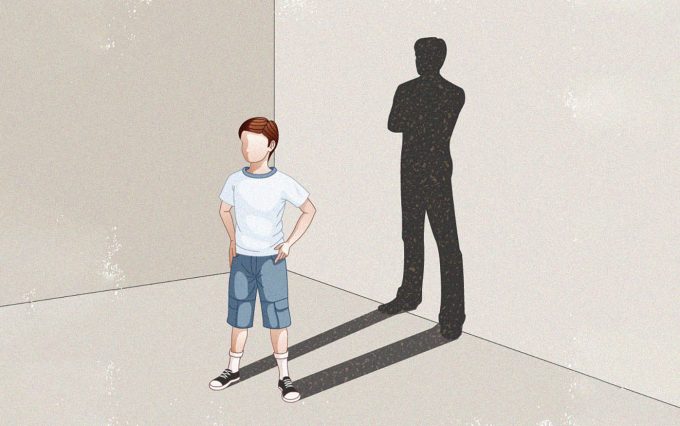

Forever to chase beauty, to long for youth is, in the end, simply to fear one’s own passing. We fear death, and we are therefore unable to grow old gracefully. We are unwilling to admit that this denial leads to distortion in our bodies and souls. Creams for wrinkles around the eyes obscure reality, Botox disfigures us, and it is woefully embarrassing, once you are past thirty-something, to show up in clothes made for members of the younger generation or to attempt to use the dope slang that all the teens are flexing. One cannot stop ageing with impunity, as Dorian Gray reminds us. A young body does not look good when draped with the experiences we accumulate over the years.

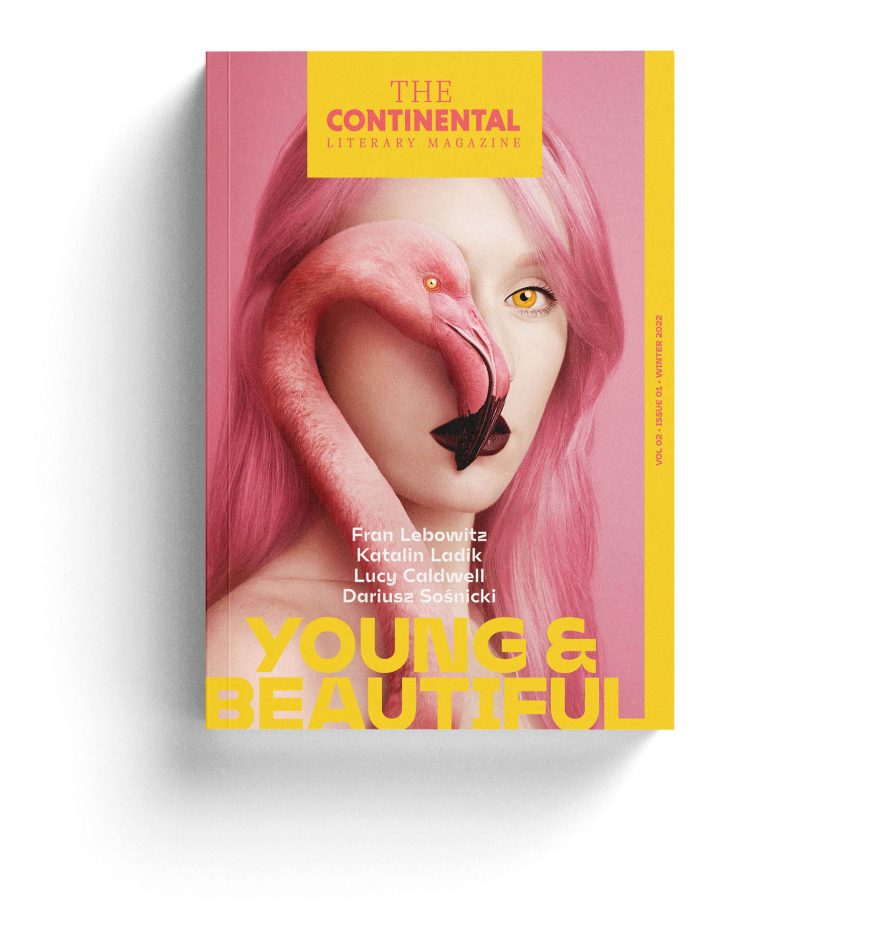

We present the Janus-faced nature of youth with a selection of masterpieces by Flóra Borsi. Borsi has captured her own beauty and youth in pixels. In her works, she uses the self-portrait, preserving moments to look back at the passage of time at the age of seventy. She offers a unique and valuable approach in our selfish era of would-be Dorian Gray agelessness, an era in which the water from the fountain of youth is being bottled, packaged, and turned into a marketed product. Fifty years ago, turning old was uncool. Today, it is impossible.

FROM THE ISSUE

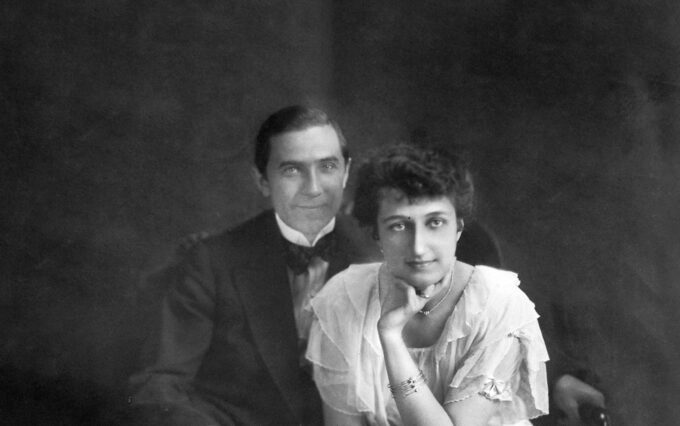

In her autobiographical essay, Noémi Saly flicks through her grandmothers photo album and learns about her affair with the legendary actor Béla Lugosi.

A group of people in a therapy session explore the more sumptuous sides of their hidden desires and touch on the intertwining of trauma and desire.

This beautiful, despairing poem about a biker is a love letter to someone we never missed and an obituary to a stranger we never knew.

A conversation with the “Princess of Photoshop”, Flóra Borsi about photography, surrealism and unconventional artistic processes – and how art can be about personal survival.

A man who fled his youth, and fled authoritarian Hungary reflects on the path, the women, and the romance that led him to maturity.

Weary and worn, Christiana Democracy considers her name, its history, and questions whether in this world a person can still believe.

Magda’s life is defined by alcohol, cigarettes, and relationships with older men as a paid companion, but can she still give her young life meaning?

In his poem, Petr Borkovec quietly, concisely, and with exacting observation sharpens out a dramatic micro-story.

Closed wards, inertia, and the summer the rivers broke their banks—a meeting between two young people in a cheap bar unearths buried emotion.

In his personal essay, Austrian writer Cornelius Hell looks back on his own youth and analyses ” personal beauty” with references to local cultural history.