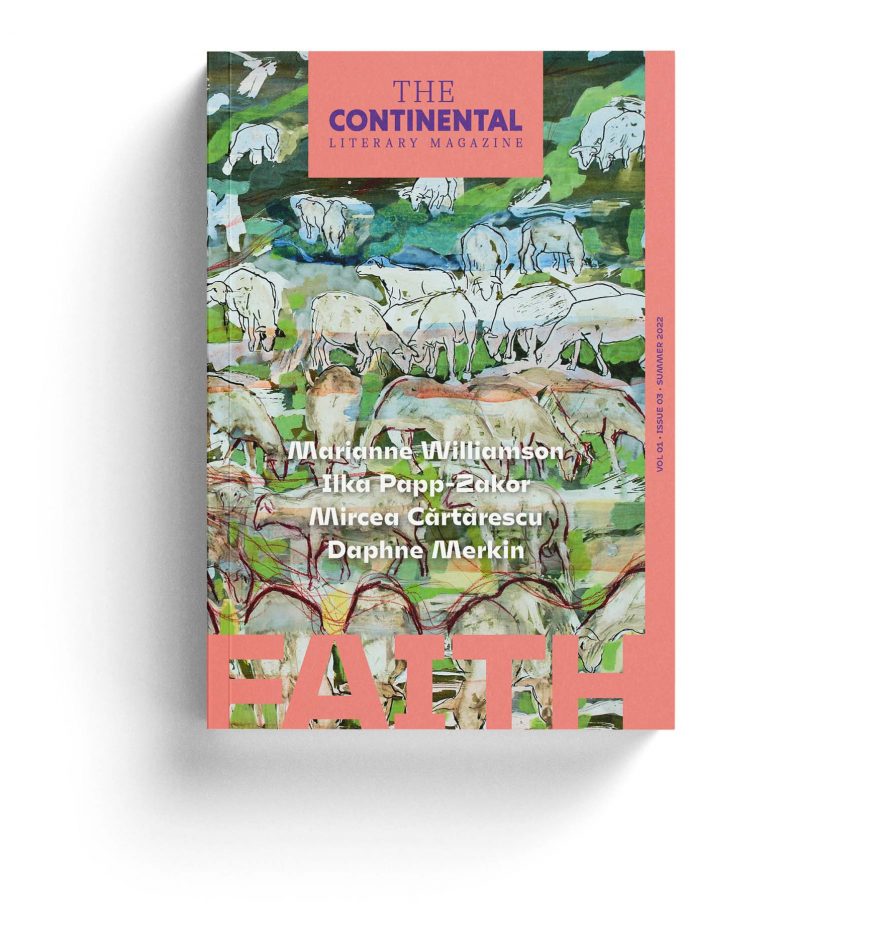

About the Issue

The Promise of Faith

Imagine our ancestors, millennia ago, roaming the wilderness. Painting a cave, chipping a stone, gazing into the fire. What faith means to them we cannot know but undoubtedly: they did believe in something. In their ability to confront deadly beasts, to trust their fellow humans, to forge alliances… that they and their children might survive another day.

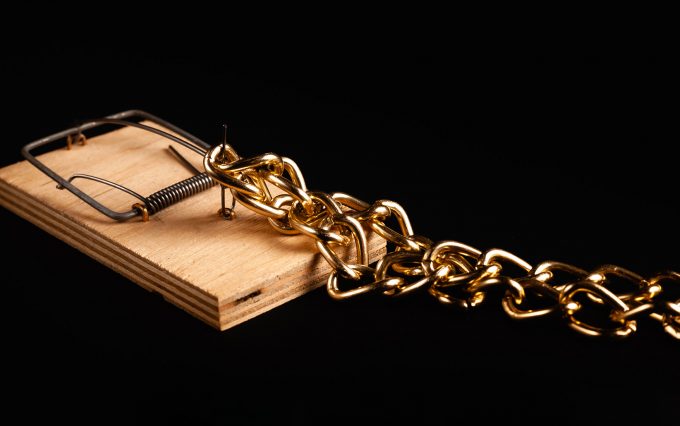

There is always the promise of light in faith, but this light often proves to be a will-o’-the-wisp that leads its followers into the bog and not the clearing. The border between faith and fallacy blurs easily. When our modern cynical mind thinks of faith, it often pictures false priests, inflamed sects, toxic ideologies. But there is much more to faith than this.

We can believe in anything: we can believe in God, in ideas, in love, in ideology, and believe in our own truth. We can believe in spirituality, just as we can believe in the rationality of science. We can believe in a higher power, but we can also place our faith in ourselves, too, and we can call that self-reliance. We can believe in others, and we can call that trust. Or we can believe in the future, and call that hope.

We all need faith in some form. Routine suffices only for the familiar. We need faith to venture into the unknown. Particularly when risk analysis, logic, and a sober mind contradict us. Without faith there is no revolution, without faith man could not have walked on the Moon.

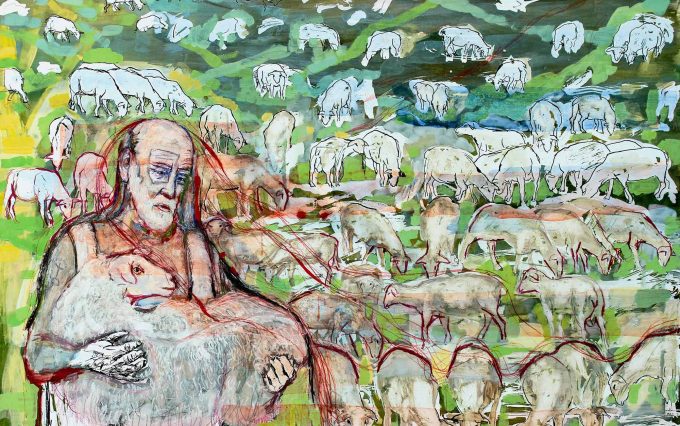

Without faith, there is no inspiration, hence there is no art. As the life and work of any artist illustrate, art is as much the product of faith as its source. Writer and spiritual leader Marianne Williamson and artist Imre Bukta, keynote contributors of this issue, were born a month apart and almost share their birthday around the time this issue was printed. Could they, one born in Houston, Texas, the other in the small Hungarian village of Mezőszemere have got to where they are now without faith? Could the young Williamson imagine that one day she would inspire thousands seeking faith? Could the young Bukta believe that his pictures would capture the imagination of his whole country and take him to America? Whatever the answer, the dream of the artist – be it the American or the Central European Dream – cannot be achieved without faith.

The Continental Literary Magazine’s focus, “Faith”, is published in the shadow of the global pandemic, the economic and ecological crises, and the war. The writings shared here remind us of the many and changing faces of faith—for which we have greater need now than ever.

FROM THE ISSUE

Imagine our ancestors, millennia ago, roaming the wilderness. Painting a cave, chipping a stone, gazing into the fire. What faith means to them we cannot know but undoubtedly: they did believe in something.

In this advice to a young poem, the speaker praises the resilience and healing qualities of mysterious, elusive, and almost shapeless poetry.

Hungarian writer György Ferdinandy, who fled Hungary after 1956, reflects on a love story in this short essay translated by Márton Mészáros.

In this poem by Ukrainian poet Iya Kiva, a “refugee-person” offers a self-definition that is as violent and sorrowful, as it is defiant and elusive.

An interview with US author, activist, and spiritual thought leader Marianne Williamson on politics and spirituality today in the US.

Hungarian writer Andrea Tompa reflects on how all faiths simultaneously desire embodiment, in an essay translated by Bernard Adams.

At Lăteşti Camp, a new arrival, Arinca, develops a reputation for her stormy love life, frequent escapes, and ability to find bodies.

“So, when I write, I should / keep your commandment—but how?” a poem by Hungarian poet Zsófia Balla, in Anna Bentley’s translation.

The Ukrainian poet Kateryna Kalytko considers the trust required to rebuild on unsteady ground, in a world between stages of renaming.

Under communism, the sculptures of the Nanai were replaced by portraits of new leaders, but communism proved less enduring than Nanai traditions.

This poem by the passionate, poetically mystical Czech poet Adam Borzič, full of images and allusions, reveals his feeling for beauty and human fragility.

In this essay, Romanian writer Mircea Cărtărescu, explores the limitations of our knowledge, and the infinite possibility of the incomprehensible.

Two boys, of very different fates, consider friendship and cruelty in this short story by Hungarian writer Miklós György Száraz.

In this essay US author Michael Rips explores the incomprehensible transcendence of God and asks, pertinently: Did Ric Ocasek Go to Heaven?

In this sometimes strange and unusual story, by Ilka Papp-Zakor, a practical joke involving a tattoo questions what we can and cannot know.

In this poem by Ukrainian poet Marjana Savka, we find the call for a realist God who fights, protects, and permits us to not forgive.

Polish writer Maciej Jakubowiak reflects on his grandmother’s absolute faith in a red blinking light, in this essay translated by Mark Ordon.

Reflecting on his own poem, Hungarian writer Árpád Tőzsér asks whether we can believe in a Cosmic Orchestra without a conductor?

Jack Kohl’s literary essay begins with a simple paradox posed by the pianist’s craft that soon transcends music into mortal and spiritual matters.

In this poem by Kateryna Kalytko, at a time of destruction, the Ukrainian poet marvels at the simplicity and the nobility of language.

In this poem, on a train winding through a burnt world towards longed-for shelter, an adult pleads to a desperate child to hold their teddy, to not cry.

While buying some “superb” illegally produced sausages, a bureaucrat tries to come to terms with the thing that lives in his office.

“collapse, rejection, resurrection, / this is what we all longed for, / this broken bread”—Béla Markó, in Anna Bentley’s translation.

“Looking for a road back to a world view that allows for sacred moments,” essayist and novelist Daphne Merkin examines her own faithlessness.

A poem by Ukrainian poet Iya Kiva in Katherine E. Young’s translation.

Father Viktor struggles to contain his rage against Prime Minister Ferenc Ács, until one day he receives a visit from men in suits.

In this poem by Kateryna Kalytko the Ukrainian poet rediscovers words, naming objects as a means of self-preservation, entering a shelter of language.

In this short story by Hungarian writer Rita Halász a mother and her partner tensely await the homecoming of her teenaged daughter.

This poem by Slovak poet Mária Ferenčuchová is a hypnotic meditation on the end and rebirth, a chillingly personal image of intimacy.

The speaker describes the sounds and movement of bugs, birds, and nature, while waiting for war, as if they were impervious to human events.

In this long poem by Ukrainian poet Iryna Shuvalova, language is found empty and ineffective, and the poet still more powerless than before.

In this novel excerpt, Krisztina Rita Molnár writes about her mother, raising four children alone, in a two-bedroom apartment in Budapest.

While reflecting on his youth, a man decides to drive his red Alfa Romeo through the night and following day, across two borders, into a warzone.

Citing martyrology, Celan, and Sachs, Olesya Khromeychuk & Uilleam Blacker ask, how can faith, hope, and love live in a space of pain? Can poetry speak of atrocity?